The £12 million farm sale and the £14 million lease

As readers of Land Matters are aware, I take a close interest in the changing face of landownership and the issues that arise from it. Scotland’s land market has been in place for centuries and the underlying dynamics of who owns Scotland deserve to be better understood.

Unsurprisingly, I have taken a close interest in the increasing amount of land in Scotland being acquired by Scottish Limited Partnerships and Limited Liability Partnerships controlled by Gresham House which, taken together, I can now confirm make them the second largest private landowner in Scotland owning over 244 landholdings extending to over 73,553 hectares of land.

Despite being the second largest landowner in Scotland, only 5 of its landholdings (covering 12,044 ha or 16% of its estate) will be caught by the “large landholding” provisions of the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill currently going through the Scottish Parliament.

This blog is inspired by a Freedom of Information request submitted to the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) which has invested £50 million in the Gresham House Forest Growth and Sustainability LP (hereinafter referred to as GHFGS). The request asked for information on the land which the Limited Partnership had acquired across Scotland. I did not make the request.

The SNIB refused the request and stated that,

We have not provided a full list of the individual holdings as you requested on the basis that doing so would potentially cause commercial harm to the Manager and their management of the Fund’s assets under the exemption contained in s.33(1)(b) of the FOISA.

Section 33(1)(b) of the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 allows a public authority to refuse to release information if,

its disclosure under this Act would, or would be likely to, prejudice substantially the commercial interests of any person (including, without prejudice to that generality, a Scottish public authority)

In this case the substantial prejudice is alleged to be to GHFGS. It is a curious decision given that all of the information is in fact available in public registers and thus the obvious exemption is that provided by Section 25 (information that is otherwise accessible). The decision has been successfully appealed.

The refusal prompted me to undertake a more comprehensive analysis of the landholdings acquired by the GHFGS.

Since it first acquisition in July 2021, the GHFGS has acquired 45 landholdings across Scotland. [1] It has also acquired a long lease on a further 715 ha (see below). All together these holdings cover 11,199 ha of land. The properties range in size from 1047 ha at Glen of Rothes in Moray (the only holding larger than 1000 ha) to 42 ha of land in Ayrshire. They comprise a mixture of farmland and established forestry plantations.

A full list can be downloaded here. You can determine for yourself what of this information is commercially sensitive.

I want now to highlight three notable issues arising out the SNIB investment and the acquisitions made by the GHFGS.

Returns

The SNIB provides patient (long term) capital to business and projects in Scotland which, alongside private investment, is meant to delver the three missions of the bank – net zero, innovation and place. The GHFGS investment was made along with pension funds and others as part of a £300 million fund.

The bank aims to achieve a 3-4% return on capital over the medium term to the sole shareholder, Scottish Ministers. However that same shareholder is also disbursing public money in grants to finance the establishment of the new woodlands being planted by GHFGS.

Up until July 2025, a total of £3.4 million of public funds has been given to GHFGS in capital grants. There will be more in future years. In fact, by 2031, a total of £11.2 million has been committed by Scottish Ministers in grant payment for woodland creation. [2]

The financial returns to the sole shareholder will be reduced as a consequence of the fact that it is providing significant public subsidy to the entire Fund (not just the sixth of the fund owned by the SNIB). In 20-30 years time, Scottish Ministers will almost certainly see a return but it will not be as high as for other investors in the fund.

An alternative means of investing £50 million would have been to invest it directly into the National Forest Estate. Of course that would have involved investing capital. The SNIB is capitalised by financial transaction money which is provided by HM Treasury. Financial transactions money is used for things like loans to households for green technology.

The money is expected to be paid back to HM Treasury and so expanding the National Forest Estate using capital is not a direct alternative. Nevertheless, it remains unclear why the SNIB has invested £50 million in a fund which is so dependent on the public subsidy provided by the SNIB’s sole shareholder.

The £12 million Farm

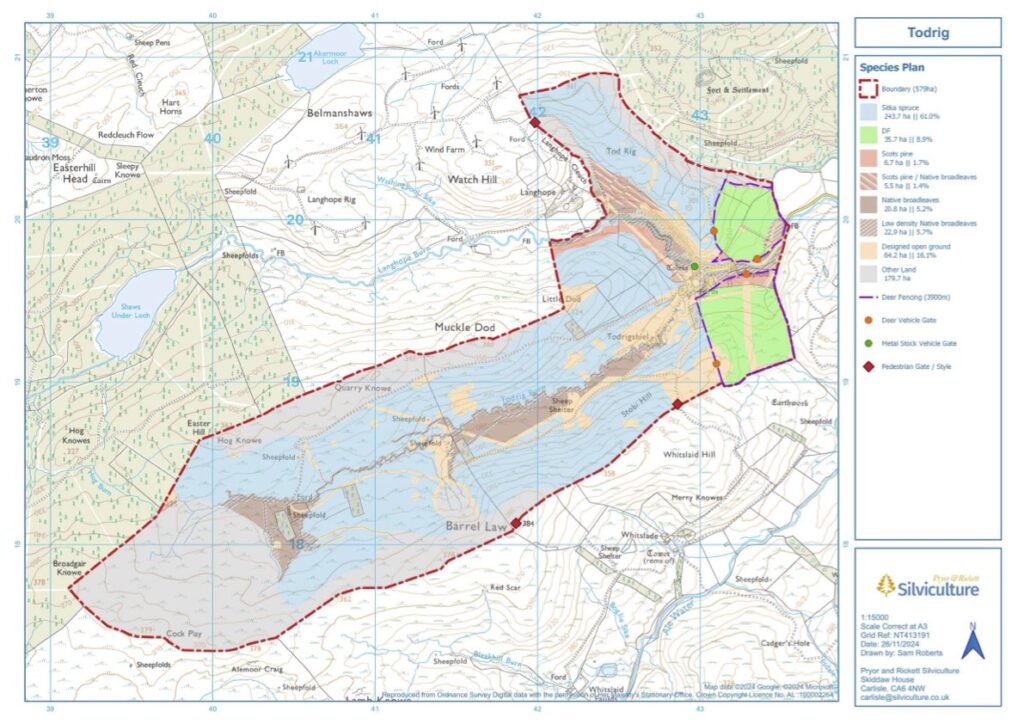

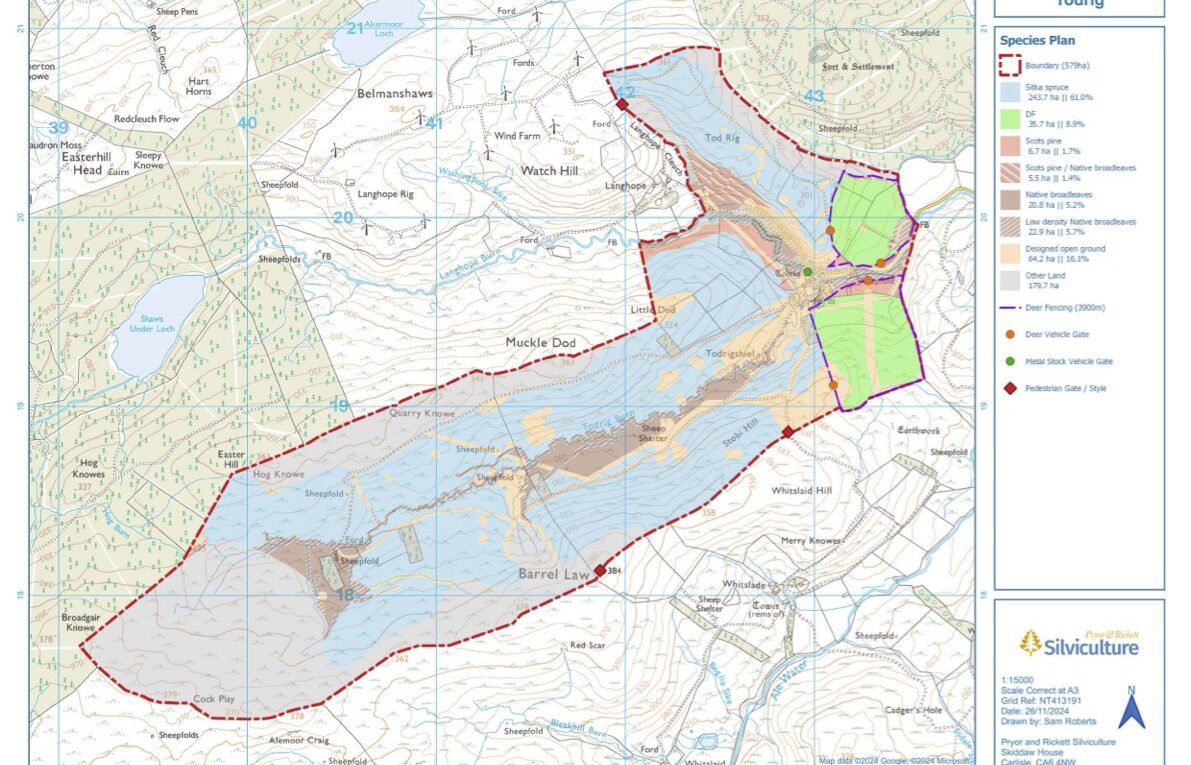

On of the properties acquired by GHFGS is Todrig Farm in the Scottish Borders. The Map below shows tree planting proposals. Click here for larger pdf.

The farm extends to 579 ha and comprises hill ground and permanent pasture. It was bought in February 2022 for £12,200,000. This equates to £21,070 per ha. This is one of the most expensive farms ever bought in Scotland and yet it is not a premium arable farm but a fairly ordinary hill farm.

According to an analysis of land values (1.6Mb pdf) between 2019 and 2023 conducted by the SRUC as part of a Scottish Government’s research programme, the price of hill land suitable for tree planting peaked at £13,590 per ha. This was dramatically up from five years earlier when it was £2500 per ha.

According to analysis published by the Scottish Land Commission on land sales between 2020 and 2022, average land prices for all farm types (including well equipped arable farms peaked at £15,152 in 2023.

Nowhere in any of these analyses does land of the quality at Todrig ever come anywhere close to the £21,070 per ha paid for it by GHFGS.

A neighbouring farm of very similar quality is currently on the market. Langhope is 325 ha in extent and is being marketed at offers over £2 million or £6152 per ha. If the farmhouse and other residential property are included it works out at £9500 per ha. [3] The buildings at Todrig are in a fairly dilapidated state.

Todrig was sold as a consequence of the divorce of the farming couple who sold it to GHFGS. Their divorce played out in public in the Court of Session where the parties agreed that the value of Todrig in January 2019 was £1,862,500 or £2216 per ha. [4] The comparison between the 2019 valuation and the 2022 sale price is shown below.

| Year | hectares | Valuation or Sale £ | £ per hectare |

| 2019 | 579 | £ 1,862,500 | £ 2216 |

| 2022 | 579 | £ 12,200,000 | £ 21,070 |

In the space of 3 years, the price had inflated by over 500% and substantially in excess of even the average price for arable farmland at the time.

I wondered whether the price reported for Todrig was incorrectly reported. Perhaps there was a decimal point out of place and it should have been £1.2 million. I contacted the Registers of Scotland and they confirmed that the consideration reported to them was £12.2 million. I then contacted Gresham House seeking a factual check of the figure. Rather oddly, despite the price being in the public domain, they replied “no comment”.

It remains to be seen whether the purchase of Todrig at such an inflated price was a sensible investment or not for Scottish Ministers, the sole shareholder of the SNIB.

Interestingly, in an evidence session before the Economy and Fair Work Committee of the Scottish Parliament on 24 September 2025, the Chair of the Bank was asked about the GHFGS investment at Todrig and the concerns of local people. [5]

Willie Watt claimed that the reason that SNIB got involved was that the GHFGS planting schemes would have a larger percentage of native species. This is the reason why the fund needed the help of an investment bank. This is the first time I have heard this claim. I am not sure it is true. The species composition at Todrig is 70% commercial conifers with Sitka Spruce comprising 61%, not far short of the maximum percentage allowed of any single species of 65%. See map above.

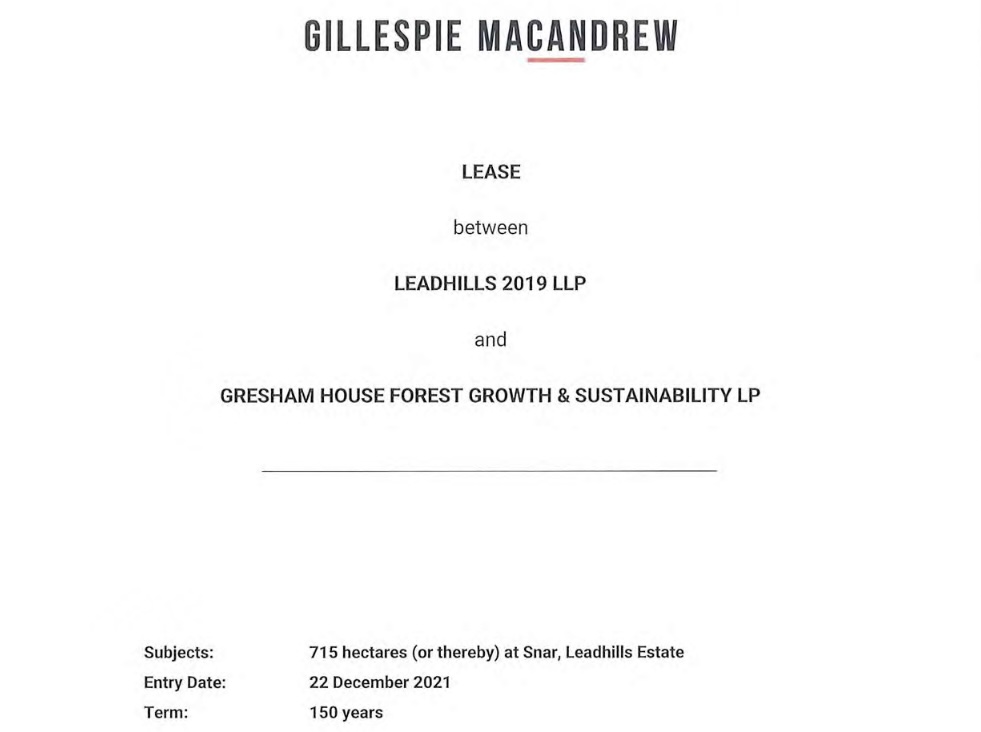

The £14 million Lease

Normal forestry investment involves buying an existing forest or bare land for afforestation. Occasionally, existing forests will be leased on long leases. Parts of the National Forest Estate, for example are leased from private estates on long leases. The most recent example is the 150 year lease of 9541 ha around Loch Katrine from Scottish Water to Scottish Ministers. It is unusal, however, for the private sector to take on long leases for afforestation. GHFGS has, however, done precisely this.

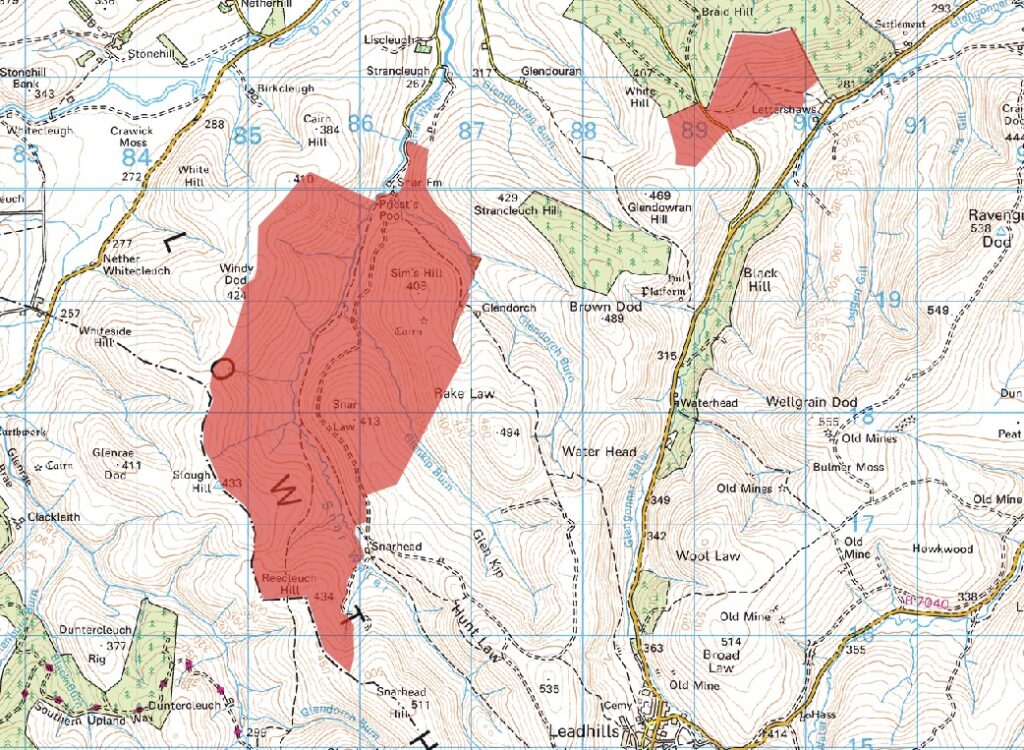

Leadhills 2019 LLP (a limited liability partnership controlled by the Earl of Hopetoun) has leased 715 ha of Snar Farm (see map below) on the Leadhills Estate in Lanarkshire to GHFGSF for at least 150 years. A grassum or premium (a capital sum paid at beginning of lease) of £14,820,009.60 was paid for the lease with an annual rent of £100.

The plan, according to the lease, is to grow commercial crops of timber on four rotations. The tenant shall renounce the lease “from and after” the sooner of 150 years or the point at which the fourth rotation is felled.

The purpose of the lease is for “growing, (and where applicable) harvesting and extracting trees” and “carrying on any non-construction activity on the subjects which may be required as part of any natural capital opportunity”. Minerals and “vermin control” are reserved to the landlord.

Importantly, the lease also confirms that “the timber crop shall, notwithstanding any rule of law, practice or understanding to the contrary, belong to and be the sole property of the tenant.” This is an important provision since, as a matter of property law, trees and timber belong to the landlord.

Interestingly, the capital sum paid for this lease (the £100 annual rent is nominal) equates to £20,727 per ha which is almost exactly the same as for the ownership of Todrig Farm. But whereas the capital value of Todrig represents an asset on the balance sheet of GHFGSF which will hopefully provide a capital gain when sold, the £14 million for Snar has to be justified purely on the basis of the net discounted cash flow from forestry products and carbon credits from the 715ha of Snar Farm. It is hard to see how this will be possible.

By comparion, the grassum or premium paid by Scottish Ministers for their lease of Loch Katrine estate was £1,570,000 for 9541 ha. This equates to £164 per ha, less than 1% of the per hectare premium paid by GHFGSF for Snar. The annual lease payment for Loch Katrine is £1000.

Perhaps some reader of this blog can explain this business model and whether it is likely to be adopted more widely.

Finally, given that Gresham House would not even confirm the price they paid for Todrig, I have not sought their response to the above thoug they would be welcome to respond and I will publish their response.

NOTES

[1] I have attempted a comprehensive search but may have missed one or two.

[2] figures sourced from FoI release

[3] The sales particulars can be downloaded here (9.4Mb pdf). Note that Langhope includes a wind farm but the sale and associated sale price are based upon the vendor retaining the income.

[4] Edith Bradbury vs Craig Bradbury 2021 CSOH 1134 at [2]

[5] See the interaction at 09:57 on Scottish Parliament TV

An Official Report of the meeting will be available.

There is also a crowdfunder to raise funds for a judicial review of the decision not to require and Environmental Impact Assessment of the tree planting proposals.

Andy, hope you’re well. Another incisive piece that perfectly captures the surreal financialisation of Scotland’s land.

Your analysis of the £12m sale and £14m leaseback is the clearest case study yet of a phenomenon I’ve witnessed firsthand while trying to acquire land for genuine conservation: the creation of a natural capital speculative bubble.

My experience with the Woodland Carbon Code (WCC) and Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) markets confirms that this isn’t just land trading; it’s a fundamental re-engineering of land as a financial instrument. Upland estates are no longer valued for their agricultural, tax dodging or ‘sporting’ potential, but as factories for producing environmental commodities.

The Financial Engine of the Bubble

As you’ve identified, the driver is the ability to calculate the Net Present Value (NPV) of future ecosystem service revenue. With WCC credits soaring from £5-8/tonne to £20-30+/tonne, a single large estate can now model millions in future carbon income. When you layer on the potential for BNG credits (selling at £30,000-£40,000 per hectare for high-value habitats), Natural Flood Management grants, and other public subsidies, you create a “perfect storm” of speculative valuation that completely detaches price from productive capacity.

The New Buyer Profile: Global Capital, Not Local Stewards

The market is now dominated by actors with entirely different motives and capital reserves:

Natural Capital Funds: Specialised investment vehicles treating land as a portfolio asset class.

Corporates & Banks: Engaging in “insetting” by directly owning land to offset their emissions, effectively vertically integrating their supply chain for ESG compliance.

High-Net-Worth Individuals: Chasing a “green legacy” and tax-efficient wealth preservation, spurred by instability in other asset classes.

These entities are not just outbidding local communities and farmers; they are operating in a different economic universe altogether.

Political Complicity and the Inevitable Populist Backlash

You are absolutely right to point the finger at political facilitation. Both the SNP and Labour have hitched their green credentials to this model of private finance, believing it’s the only way to meet climate targets without public investment. In doing so, they are actively enabling a system that holds the public to ransom—we must either pay inflated prices for ecosystem services or fail to meet our legal environmental commitments.

This is not a stable system. The bubble will pop. It will likely burst when a combination of factors collide: a future government U-turn, a scandal over the validity of credits, or—as you rightly hint—a populist backlash from a Trump/Farage-style movement that successfully frames this as a “green tax on ordinary people” that enriches a new elite of eco-financiers.

The Unspoken Solution: A System We’re Powerless to Implement

We know the answer. A direct Land Value Tax (LVT) would capture this unearned rental value for the public good, deflating the speculative bubble and forcing land to be used productively. A robust carbon tax at the source would be a more efficient way to drive down emissions than this convoluted, rentier-friendly offset market.

But these solutions remain politically impossible precisely because the economic forces you’ve exposed have a death grip on public policy. The Leadhills-Gresham deal isn’t an anomaly; it’s the logical endpoint of a system designed to create private wealth from public ecological crises.

Your work in documenting this is more vital than ever.

You’re a tough warrior and Scotland is lucky to have you in the front line of battle. Our so called government seem to be at the back of the line when it comes to protecting our resources from obscure foreign investors. ( I include the english in this)

I become angry when I see how our poor abused country is treated by these creatures who have no respect or care for our land, wildlife and its habitat or the wishes of local people.

I look forward to independence when we can demand far harsher laws to stop the abuse by increasing taxes , limited access to that land for foreigners …total and open intentions for the land …with local people involved at all stages. The Chinese call their land and resources ‘their treasure’. and protect it. We must do likewise.

Thank you for all your non stop hard work.

For Scotland and her weans.

Thank Andy for this. I loved showing you how to access the sasine records before your first book. Keep up the good work

So, one set of money-men get rich from selling us our own energy at inflated prices. And another set of money-men get rich from selling us carbon-credits to offset the greenhouse gases produced by the first? Oh yeah, and they also own all our land.

The real ‘business’ these people are in is extracting wealth from nation states in an ever-faster and more efficient way.

They won’t stop until they have it all and we are tramping around bare-arsed and shoe-less, just like our forebears. And our governemnt is helping them.

Thanks for this Andy

I’ve been wondering for some time why the national forest estate doesn’t lease land from upland farmers who have some marginal land on this sort of 150 year timeframe. This would save family farms having to navigate the complexity of planting grants and also managing woodlands which isn’t their thing. And also provide a tradeable lease. But I guess that requires a more proactive state. (I’ve also been wondering why we’re not using the extensive land in public ownership to generate publicly owned renewables but obviously I don’t really understand the modern world).

There is indeed much to wonder about!

Good questions Pete.

I guess if we leased the land from farmers we would have to pay for the lease and create the woodland? And we don’t have the public money available for that?

Or could we gently remove the high agricultural subsidy for sheep and replace it with use the money for woodland creation which would be more productive financially and for the public good. I appreciate there are real farmers out there but would they be open to this if we provided training and support for example. Even with the subsidy many sheep farms can still make a loss especially if you take into account unpaid family labour.

Publicly owned renewables. Presumably most of our publicly owned land suitable for this is used for forestry. Could we put renewables on some of that land and still use it for forestry? Massive capital investment in a windfarm, complexities and risk though. Given public investments can and do go spectacularly wrong could we work in partnership. SNIB with another investor(s)?

https://forestryandland.gov.scot/what-we-do/renewable-energy-in-scotlands-national-forests/further-information-on-renewable-energy-developments#:~:text=Routine%20management%20of%20forests%20continues,not%20consult%20earlier%20than%20this.

We do something at least.

Great work Andy, thanks so much for bringing all this to our attention. I agree with all the comments above.

My take on these valuations is that they represent an investment that is a reasonably secure hedge against future inflation over the long term. Inflation that is likely to be exacerbated by fiat currency devaluation (as investors view government debt as increasingly risky) and increasing disruption to global commodity supply chains (due to increasing risk of acts of war and, in the longer term, direct effects of climate change). Land upon which you can grow an essential commodity like construction timber, is a relatively safe bet, you are able to sell into future higher demand markets at future inflated timber prices. I think serious people with big money are interested in options to divest from cash-based financial assets. I think the offer is sweetened by the current carbon storage income streams in that it can offset the risks to tree growing (disease/wind throw), but investors will know this income could well be transient as it’s a political choice. These investors recognise the future value of construction timber – it will be far more directly useful than gold.

OK but if you have £14 million to invest and the choice is a 150 yur lease or ownership of land, why would youn choose the former when your future activites on both are goign to be exactly the same?

I guess their business plan recovers the £14M investment – they must see it as a minor cost over the 150 year lease. In simple terms they are paying £133 per hectare per year (at today’s prices). That may well appear to be an utterly negligible cost later in the lease period following their anticipated increase in inflation in the prices of land rent and timber (devaluation of cash). The fact that they retain title to Todrig after 150 years would be a bonus to their business plan. Either way they have £14M less in their bank account for a very long time.

Sure, but as I commented in reply to Charlie, if you have £14 million to invest, why choose a 150 year lease when you could purchase suitsable equivalent land and be the owner of that land?

The implication is that some sort of arrangement has been arrived at. The figures of £20,000+/ ha for hill land are just astonishing. It is a bubble being inflated in plain sight in front of our eyes, and the usual people who might provide for checks and balances are complicit in it. The situation has got out of hand already. There is no environmental benefit arising from this. All this money is doing is changing the names on title deeds. We have a group of naive but well meaning politicians, totally out of their depth, and and a group of speculators who have seen them coming. We need a good market correction to sort all this out.

Thanks for investigating and your work on this. It’s good to see this in the public light.

Regards Todrig:

We can’t blame any investor (Gresham in this case) for buying the land to do what we have asked them. We are offering grants for them to plant trees to create native woodland and a crop (sitka) for commercial timber within the parameters we have set. They organise and manage the project, find investors, take business risk and take a profit, which we tax, for doing so. Investors, in this case us / SNIB and pension funds invest money and make a return, on which we also tax. Is all this that not what we want, as we asking for these outcomes?

If they, Gresham, are avoiding Scottish/UK taxes then that is something else to address before providing any grants or permissions, rather preventing woodland creation and forestry as an investment itself.

In terms of the SNIB investing in such schemes may be this is a good outcome. If we the public have a stake in the enterprise then we get a say and influence things and secondly we get a share in the profits which we can reinvest in another project. By only having a stake rather than full ownership, then our public money is much less at risk. Partnership is surely a good thing where we the public can benefit from private investment and innovation.

This isn’t necessarily a high-risk speculative investment, is it? There is a land asset, grants for native woodland creation, commercial timber sales, possible biodiversity grants and carbon capture credits. Regards the price of £12 million maybe this reflects this (and the public benefited from the capital gains tax from the improved selling price)? Presumably. SNIB calculated all this before investing the public’s money?

Presumably we will save on the high level of grant for the sheep farm.

The valuation of Lot 5 at Langhope may be already reflects the fact there is an existing windfarm lease with stipulations?

Regards Gresham owning 73000 ha. It’s a lot but it is spread. Looking at it from a monopoly position in Scotland, its under 5% of the 1.5million ha of forestry land, and about 1% of total land so not anywhere a monopoly, and the Scottish Ministers have 30% of forestry land.

Hi Andy,

How is the £12m price tag arrived at? Are there underbidders, as there might be in a house sale? Or did Gresham H. decide how much this parcel of land was worth to them, and come up with an offer?

I have no idea. Only Gresham House could answer that question.

It’s a farce isnt it, and greenwash to boot.

Scotgov provide carbon credits to plant Sitka forest, when the latest science suggests that no amount of carbon capture by Sitka will offset the carbon loss from any peated and marginal bog land.

It’s a governmental slight of hand that means land is being owned and exploited by foreign investors (In this case Gresham House who are owned by a North American money group)