Dùthchas and the Road Home

Guest Blog by April Cumming

April is currently based in Melbourne and works for the Australasian Housing Institute supporting workers in the community and social housing sector. She worked for Malcolm Chisholm in Holyrood from 2011 – 2016. In 2026 she will commence a Masters of Public Policy with a focus on Indigenous Sovereignty and Contemporary Land Policy. She writes here about her personal experience of growing up in Lochaber and the need for land reform to re-people the Highlands.

For many people living in communities in the West Highlands of Scotland, our music, politics and the way we think about land and ourselves is tied up in a word – “Dùthchas”. It is the hook that draws us back when we travel away, and it creates the space that holds us close when we return. It speaks to two fundamental basic human needs; to have a home, and to have community. In the summer of 2024 I returned home to Lochaber, looking to understand current attitudes to how land is owned and managed, and whether conversations in the Scottish Parliament on new legislation represented the experiences of those most affected.

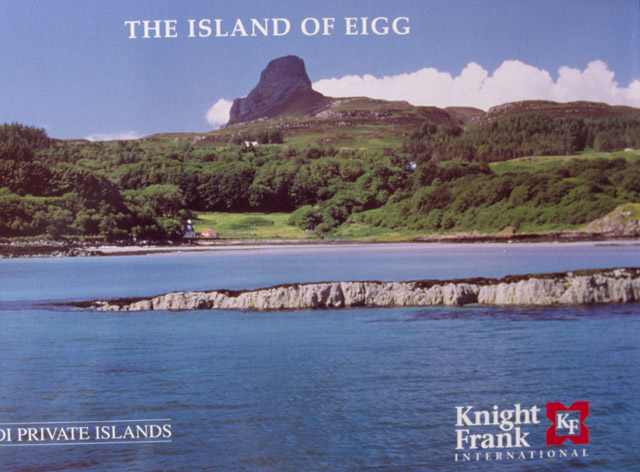

My journey started in the Island of Eigg, where light and darkness balance on a knife’s edge, depending on the time of year. The Eigg Community Buyout, won in June 1997, captured the hope and imagination of thousands of supporters, tired of witnessing the familiar story of absentee landlordism and mismanagement. The victory was a momentous moment for the Island, and for Land Reform advocates nationally.

“A lot of properties were tied to working on the estate, and that security issue was a big part of it. Jobs on the estate tended to be seasonal, insecure and without any contracts” says Maggie Fyffe, the Secretary of the Isle Of Eigg Heritage Trust, and the stalwart who helped kickstart the campaign for community ownership. The community had witnessed a decline in living standards and access to resources for decades and had been mulling a buyout for years by the point of 1995. When an eccentric German artist, already mired in debt, purchased the island that year it was the final straw.

“Before Maruma (the artist) bought the island we had gotten ourselves together and organized workshops with a member from every household”, continued Maggie, “we split into small groups to choose one or two topics every night. Tourism, agriculture, etcetera… We had a good community view on things before we were at the point of making a bid.”

Lucy Conway, a trustee who helps drive growth and investment in the community, adds “There’s a lot of talking, either formally or informally. If you decide that you want to move ahead with a community buyout, know first what you’re doing it for, and do the work of finding that out collaboratively. The most practical thing always comes to the surface; how are we going to do this, how are we going to make it happen and keep making it happen”.

Despite the steps forward taken by buyouts like Eigg, Assynt and Knoydart, private landowners in Scotland are consolidating their dominance over huge swathes of the country. As I travel through the West Coast of Scotland, speaking to friends and former colleagues in politics, the need for more radical reform becomes abundantly clear. A recent review of ownership conducted by leading land reform expert Andy Wightman found that: “private rural landownership has become more concentrated over the past 12 years with 421 landowners owning 50% of the privately-owned rural land in 2024 compared to 440 in 2012” and that a

staggering “ 83% of rural Scotland is owned by private entities”. This imbalance has huge

consequences for local democracy and power structures.

On my journey between Eigg and Inverness, I pass through endless rolling estates with grand homes placed smugly near lochs or beaches. These fiefdoms either pass through generations without challenge or change, or are bought at a princely sum to facilitate cosplayed forays into tweed and tartan.

A few people guard over this land, determining the destiny of the soil below and the boundaries of the sky above. Here, a market-led system of ownership has created abundance for a few and insecurity for many. It has resulted in Scotland now having the most concentrated pattern of private land ownership in Europe.

Between the estates, and throughout the West Highlands you cannot miss the scattered signs of previous life, with stones that betray the land’s legacy of forced evictions. Roughly 160 years ago, the way land was managed changed dramatically. With rising levels of personal debt, landowners and Clan Chiefs saw there was more money to be made from industrial scale livestock grazing to clothe the workers of the industrial revolution in the cities. Tenants paid high rents for remaining on the fertile land or were driven to overcrowded collections of crofts on the coastline, where land was less fertile, and they had to work for pay. This process displaced people and ultimately reshaped the power balance in

the interest of capital and empire.

This brutal history, and the sheer iniquity of ownership now, continues to moves people to take action for real land reform. At Inverness station I meet with Rob Gibson, a long-term advocate for community ownership and a former Scottish National Party (SNP) Member of the Scottish Parliament. Rob was Chair of the Rural affairs committee that stewarded in the Land Reform Bill of 2016. He has played a large part in agitating for progress from within the government – further legislation, the draft Land Reform Bill (2024), is currently under scrutiny.

We discuss the bill in its current form, and the capacity for further progress and consensus within Holyrood.

“We are lucky in that (in the Scottish Parliament) we’ve always had an 80% majority in favour of reform, and it is possible to pass things”, Rob highlights. “The current legislation looks at the size of land holdings and ways to make landowners accountable. It’s a step forward. However, the bill needs to have more than environmental and climate change impacts as the key focus. There must be the ability to use land more effectively for things like affordable housing.”

When I ask how future reforms could facilitate more housing, allowing people to live and work locally, Rob points to taxation of land as a lever for change.

“Legislation has to include taxation to drive change. People who own large amounts of land often pay their taxes in places like Denmark, for example. If you had something like Land Value Tax, they would pay here.”

In what Rob terms a ‘housing emergency’, we require more than one-off penalties for a failure to follow the rules. We must shift away from the market-led approach to ownership that places the right to accumulate property above the sustainability and wellbeing of communities.

Leaving Inverness, travelling South via the East Coast, the landscape changes and evens out into rolling fields. Farmland, portioned neatly along the horizon, offers up the fruits and shoots that supply our major retailers. As the berry fields roll by, songs from my childhood return to me. Songs that were written by working people, who lived on the land without ever having ownership.

The session culture of the West Highlands was peppered with songs and stories, often in Gaelic, about people whose feet were planted deep into the land, but who often lacked the legal support, privilege or even paperwork to remain standing. The thread of our own understanding of colonialism and the accompanying sense of disenfranchisement ran from history books, into pubs and community halls, and right into our own homes. It was centered in the stories we learned at the yearly Feis. It was real and present. We lived in the most beautiful place, but peace for so many was predicated on seasonal employment, and the only certainty was that our material situation might change in a moment.

As fate would have it, our situation did change. Without legal documents, my parents had to leave our home of 25 years, a much loved but essentially condemned 100 year old de-crofted house. The circumstances of their loss is not my story to tell. But I can tell of the wrench in my stomach that came with closing the back door for the final time, and sitting in the garden for one moment more, the grass under my fingertips. I can tell of the heartbreak of knowing that my christening tree, a healthy cherry blossom, would grow on without me. That memory of love and connection, and the accompanying grief of loss, is what I understand ‘Duthchas’ to be.

On to the central belt, and Glasgow greets me with whisky and friendship. Dr Josh Doble, head of policy at Community Land Scotland (CLS), joins me at University Café, a formica sanctuary where students and academics conspire to revolution over peas and vinegar.

CLS actively campaign for extensive reforms to land ownership, and support communities to advance their own buyouts.

“The key mechanism that we (CLS) were looking for in the bill was a public interest test, applied at the point of sale or transfer”, Josh highlights. “We wanted legislation that would really look at who the owner was going to be – are they tax residents in Scotland? Do they own other plots of land, what were their plans for that land? The government or the land commission would then make a choice about whether that purchase was in the public interest“.

It is clear that the bill, as drafted, has significant shortcomings. While new legislation to improve accountability on land use by owners is welcome, the measures seem to be more about enforcing consultation than real redistribution of what should be a public good.

“At the moment we see a lot of commercial projects, natural capital or forestry projects, that don’t do much for local economic development or the local community. Neither do they really secure many benefits for Scotland as most of that capital is then extracted out of the country”, Josh continues. “A strong public interest test is about making the government decide on landownership and management. For example, how does commercial tree planting impact the community around that estate and does the ownership deliver wider public benefit? That’s healthy and democratic.”

Walking away from our meeting I feel buoyed by the optimism and commitment of organisations like Community Land Scotland. Member-led and collaborative structures are central to driving campaigns for change, and many voices together have a chance of being heard.

My journey continues to Leith, where I once worked for the local MSP, Malcolm Chisholm. The familiar streets and bars are here, with the addition of tram lines and artisanal coffee. I recognise the spirit of the people’s republic, spilling out of the Port of Leith bar onto the hot pavement. Here I meet Malcolm Combe, a Senior Lecturer in Law at Strathclyde University and a leading academic in the space of property law and land reform.

Even with his extensive reading, and well exercised analytical practice, it seems Malcolm has faced similar difficulties as I in navigating this dense legislation. I wonder what this might mean for residents wishing to use provisions to enforce their rights. How might a tenant use this Bill to report a landlord when they fail to disclose a sale?

“When you pick up the bill and think, ‘right what does this do for me?’, you need to first understand, for example, how the pre-emptive right to buy works in advance’, highlights Malcolm. “And when it comes to the groups that qualify to report on non-compliance (by landowners), who can be a designated clype?”

I ask how the land reform bill could be improved, so that it can be interpreted and used by those who stand to benefit from it.

“There’s not one big ticket fix. Community right to buy is predicated on there actually being a community in the first place – one that has the social and economic capital, with people who have time to organize, to do what needs done.”

Essentially, for any reform to be effective, there must be adequate support and resources on the ground to make it happen. Malcolm touches on these barriers to participation and wider issues in his substantive blog piece on ‘Basedrones’.

Across Scotland, hard pressed communities need real land reform to build, live and work locally. However, without a great deal of time and access to legal support and resources, the barriers to engagement are still too great. If land reform is going to be delivered by communities, then there needs to be a recognition of the pressure that communities are under. Land reform will not be delivered in a meaningful, national way if communities are not properly resourced and supported. Only then can we build a system of ownership that is

more sustainable, that brings value back into communities, and serves as a bridge to re-people the West Highlands. As a country we must recognise that land is not simply a private commodity – it is our shared memory and our shared future.

I finish my journey driving through Glencoe, back to the West Highlands and the centre of my own history. In Garvan on Lochiel side where I grew up, I visit the home of my oldest high school friend. She has just secured a croft for her family, and has already amassed dozens of chickens, cut back bracken across the hillside and made space for pigs to turn the soil. She talks about looking after the abundant crop of rowan trees, because as we know rowan trees ward off bad luck. Nearby, her parents have their croft, and slightly further along the shore her aunty and uncle have theirs. In the evening we open a Harris whisky and revisit

some memories, at a kitchen table not unlike the one from my childhood. This ‘Duthchas’ is a felt experience – a moment of recalling community, or as Rob Gibson would put it ‘re-remembering’, that grounds us in place and then stays with us when we go.

Through the window the sun sets behind familiar mountain peaks, reflected in water and shining granite. The air falls silent, punctured only by the Fort William – Mallaig evening service which cuts a silver line through the hillside.

A few miles up the single-track road, in a darkening field, the place I once called home sits. A place that once held love and song, now overgrown by a beautiful garden, in the shadow of a 41-year-old cherry blossom tree, whose roots run deep.

Inspiring, taing mhath

I’ve got a lump in my throat reading this insightful analysis.

So many missed opportunities for real and meaningful change that would centre the interests of the people who live and work in the area. We are up against a very well organised, monied and super-connected lobbying group and unfortunately our legislators seem to be no match for them.

Stunning snapshot of the tyrant of late capitalist wealth centralisation and geocultural exploitation. The terrain of the western highlands is evoked so gorgeously while a spiritual dagger runs deep into my collectivist communitarian soul.

Its a disgrace that the SNP has been in government for nearly 20years and has failed to address the issues

Until the idea gains traction that location rent is our collective heritage and needs to be collected in full instead of taxes on productive activity (work and trade), there can only be a marginal positive impact on Scottish life. See #ATCOR.