Has Craiganour Estate has got away with a criminal offence?

In my blog yesterday, I reported a breach of rules introduced to improve transparency in landownership. I have reported the matter to Police and will be reporting back here on progress. Meanwhile, I am pleased to publish this guest blog by Alan Brown which documents his own odyssey in trying to enforce the regulations.

Guest Blog by Alan Brown

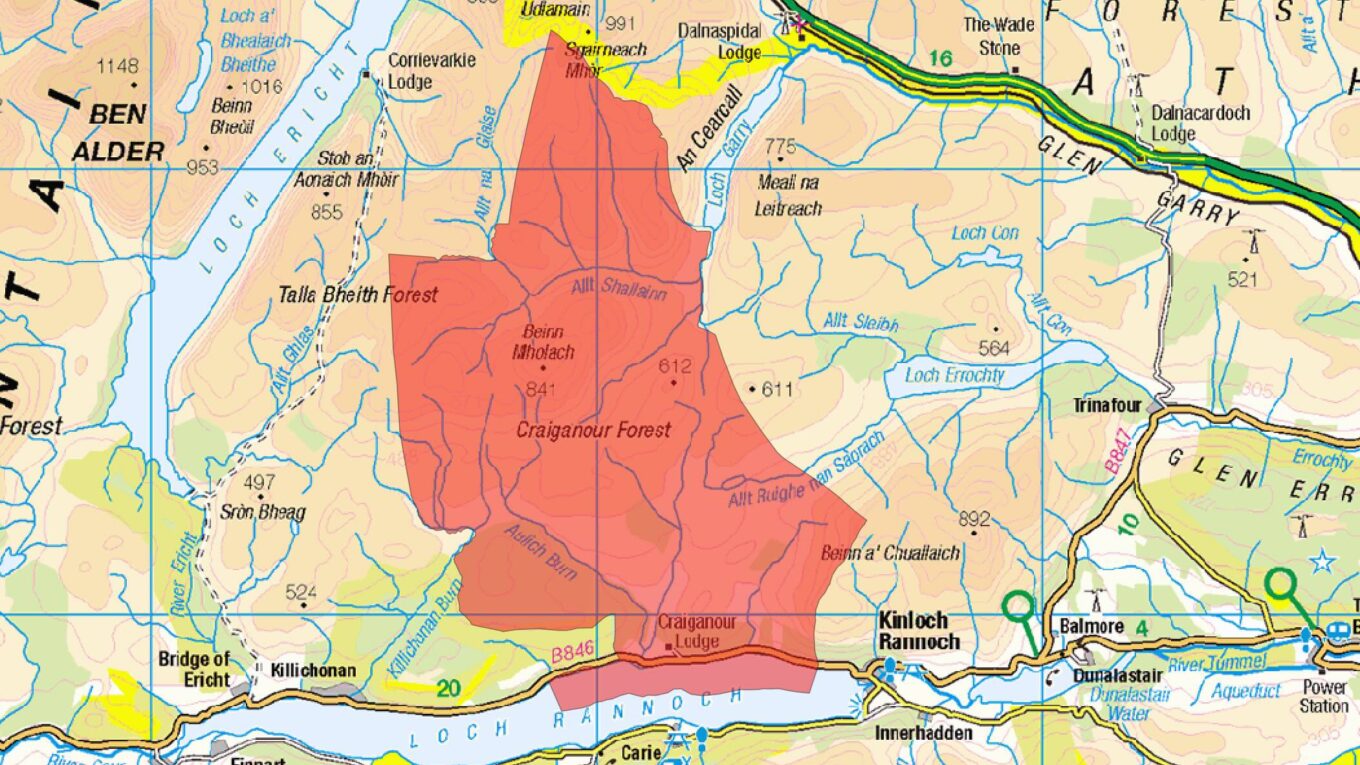

In the summer of 2016 I was sitting outside a bothy on a grassy knoll in the heart of the long-deserted hamlet of Duinish in Highland Perthshire when a four-by-four vehicle appeared. Two women emerged, one of whom bashfully accepted that she was the owner not just of the bothy and the knoll, but of all the surrounding hills. Or rather her husband was.

The lady was charming and even offered to bring me dinner from the kitchens of the lodge at Craiganour, on the north shore of Loch Rannoch. I didn’t want to seem rude given that I was spending the night in her bothy so I didn’t ask who her husband was, despite my curiosity.

When I got home, I discovered that the estate and the lodge were owned by Astel Ltd, a shell company in Jersey. The main director of that company was, and still is, a financial concierge in Paris. The identity of his boss, the actual owner of the company, and therefore of Craiganour, was wholly obscure.

The topic of just who owns Scotland is a longstanding and contentious one. In modern European countries if you want to know who owns a piece of land you consult the ‘cadastral map’, held by the local town hall or regional government. This has been the case since the Napoleonic era but has only been even partially true in Scotland since 1981 when the Land Register of Scotland was established.

Because this register only records land transactions since 1981 -2003 (counties went “live” in a rolling programme from Renfrew in 1983 to Sutherland in 2003), in order to know who owns some land in Scotland you still have to consult the Register of Sasines, which was established in 1617. It records not ownership as such, but deeds relating to ownership (transfers, standard securities, bonds etc) and it is up to the enquirer to come to a conclusion as to who does or doesn’t own the land in question.

Consulting both the record of Sasines and the Land Register is only possible on payment of a fee. Additionally, there wasn’t until recently any legal reason why land in Scotland couldn’t be held entirely anonymously through an offshore holding company or a trust. The whole system was stacked in favour of landowners – whose lawyers had created it against the interests of the ordinarily curious Scottish citizen.

In 2016, in the wake of the 2014 referendum on Scottish Independence, the SNP swept to power at Holyrood and with them came at least a part of the groundswell of indignation at the way upland Scotland is used for shooting and fishing by aristocrats and international plutocrats.

Fast forward to 2021 and the Scottish Government published a statement on land rights and responsibilities. They promised ‘transparency about the ownership, use and management of land’ and that this information would be ‘publicly available, clear and contain relevant detail’.

The way they chose to bring this transparency about was a set of highly complex rules and an online database. The rules are the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 (Register of Persons Holding a Controlled Interest in Land) Regulations 2021. It’s fair to say that they didn’t trouble the television news when they came into force, let alone the public consciousness. They make it illegal to control land in Scotland anonymously except in certain circumstances, on pain of a fine up to £10,000.

After several grace periods the new law came fully into force on 1 April 2024. On that day I entered ‘Craiganour’, its postcode and its Land Register number in the online database. Nothing. There was no entry, no owner and no controlling ‘associate’. There was a 30 day period for pending entries so I tried again after that. Still nothing. I tried again today (8 May 2025) – still nothing.

I wrote to the Keeper of the Registers of Scotland who host the Register and asked if she could help. She couldn’t. I tried the Scottish Land Commission, the Scottish Lands Tribunal and the Cabinet Secretary who had sponsored the new rules, Marie Gougeon.

None of them would make any useful comment beyond telling me to call the police if I thought something was wrong. It seemed unlikely that the police were responsible for a land registration database but with nowhere else to turn I filled in their online reporting form. In return I got a call from a very polite lady in Inverness whose job it clearly was to get rid of people like me. But I persisted and got an appointment to talk to officers in Edinburgh.

One of the few people to emerge from this story with any credit was the officer I spoke to in Gayfield Square police station. PC Do Rosario not only didn’t laugh me out of the grubby interview room, he examined the law I’d printed off for him along with the four page dossier detailing all the information in the public sphere about Astel Ltd and Craiganour.

That doesn’t amount to a whole lot, but we do know that amongst Astel’s owners are two anonymous trusts in the British Virgin Islands. We also know that the UK manifestation of these trusts is a named tax minimisation specialist in the City of London. I supplied his name, address, number and photograph and along with the same details for the main director of Astel, Jonathan Benford of Benford Lemaître, a firm of Paris wealth consultants specialising in advising UK citizens resident in France.

The investigation took off slowly. No one had ever reported the offence in question before. PC Do Rosario had to have it added to the drop-down lists on the police computer and check that the whole thing really was a police matter with the Procurator Fiscal. At that point I realised that the Scottish Government might have neglected to inform Police Scotland of their new responsibilities.

Eventually the case was passed to another uniformed officer in Perthshire. He seemed nice enough, but the law is complex and to know whether an offence had been committed or not this officer had to dig out some quite obscure details.

Amongst these were whether or not shares in Astel were traded on any stock exchanges in the European Economic Area. So a rural response officer with responsibilities for livestock on the roads, domestic violence and so on was tasked, notionally at least, with checking the Icelandic stock exchange, the Kauphöll Íslands.

Another means for the controllers of land to avoid revealing their identity under the new law is if they have less than a quarter of the voting rights in a holding company. Jersey, however, is a secrecy jurisdiction quite outside the powers of Police Scotland to compel the disclosure of voting rights. Nobody outside the directors and owner of Astel know how it’s structured, and the police in Perthshire would have to get specialist resources to begin to investigate the matter.

What finally ended the police investigation was yet another perfectly legal means of escaping disclosure, namely the ‘security declaration’ under which the owner or controller of land in Scotland can say that being forced to disclose their identity would put them at risk, or threat, of violence, abuse or intimidation.

The declaration can be seconded by a range of professionals, including a ‘registered nurse’. The law doesn’t specify in which country they have to be registered, but their say-so is enough to cloak a Scottish landowner in secrecy for five years. Not only that but the Keeper of the Registers of Scotland has declared that the security declarations themselves are secret. And not just secret from us but secret from the police and the Lands Tribunal Scotland which has the responsibility for making judgements as to their validity.

Given that the police have no idea if the owner of Craiganour has a security declaration in place or not and no means of finding out, they simply decided that they had more fruitful things to investigate. My complaint was duly classed as ‘no crime’. The practical upshot is that in Scotland you can get away with the crime of failing to say who you are by the simple expedient of not saying who you are.

At this point I was free to phone Mr Benford, the wealth manager who directs Astel Ltd without stepping on the toes of the police. In a tone that suggested he’s unused to dealing with impudent enquiries, he stated that his doubtless fragrant clients “have a right to privacy”.

Pressed, he suggested that the registration process was underway after some confusion between English and Scots law and that “all will soon be revealed”, something which may or may not be true, but which changes nothing here either way.

Craiganour is just a test case. There are tens of other sporting estates in the same situation. I learned nothing from Mr Benford, except that the police had never phoned him, judging by his surprise at the mention of Astel and the British Virgin Islands.

So, what exactly has gone wrong with the law in Scotland?

The legislation was drafted by the civil service, put out to public consultation, considered by two Holyrood committees and passed by the Scottish Parliament and yet is unenforceable by the only body capable of enforcing it, namely the Police. All the airy patrician declarations to the contrary were for nothing. We have every right to be furious about this.

The current Scottish Government gets a great deal of flack for the way it has handled complex projects such as the procurement of new ferries and the expansion of the A9. Those two issues involve all the complexities that come with dealing with outside agents, commercial contracts, supply chains, the weather and commodity prices. This, on the other hand, is a debacle entirely of their own making.

The legal structures around land in Scotland are in the gift of the Scottish Parliament and government to make. There was never any time pressure or any outside constraint in the drafting of these regulations. Where the ferries and A9 are like football, with the ball coming at speed and fought for, land reform is more like snooker. The ball sits still, and the player has all the time in the world to demonstrate their skill. So just why did the Scottish government, produce a legal and administrative structure which has no beneficial effect in the real world?

The answer may lie in their closeness to landed interests. The landowners of Scotland formed a private limited company called Scottish Land & Estates to represent their interests. Its staff are frequent and highly successful contributors at committee and consultation stages for any Scottish legislation touching on land. Craiganour may or may not be a member of SL&E. I contacted them for comment on this article but they declined to give any.

My initial attempts to get information on the new regulations from the Scottish Government were met with a barrage of incomprehension, irrelevance and obfuscation. Civil servants failed to answer my questions and instead answered questions of their own invention. I got no sense at all until I made a formal complaint and then it became very clear that while a lot of thought had gone into the rules from the landowners’ perspective, none at all had gone into their operation from the public’s point of view. This despite the vigilance of the public being the only mechanism by which breaches of the rules could ever be detected.

I offered to meet Ms Gougeon to explain what I had found out by testing the law she championed, but she had no time in her diary for that. I got the strong impression that no one in the grand Victoria Quay offices has much interest in what actually goes on outside its walls.

And despite the many millions spent on the Registers of Scotland, the Scottish Lands Tribunal and so on, not one public body was given the job of policing the new register. That was left to the initiative of citizens like me and the police if we dared report matters to them.

Nor was any guidance produced on the thickets of conditions and loopholes, except from the perspective of the landowner. I do think the civil service has to bear some responsibility for the operational failure of rules it drafted.

The Scottish Parliament also often seems to think highly of itself. It currently has a small display in the entrance lobby noting that its foundation has ‘created vital opportunities to modernise Scotland’s land ownership laws’. It’s certainly a pity that the scrutiny of two of its committees failed to spot that the law as, drafted and promoted by Ms Gougeon, has precisely no effect when put to the test in the real world.

The Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee expressed its intention that once the regulations were in place ‘it will be possible to look behind every category of entity in Scotland, including overseas entities and trusts, to see who controls land’. But they have failed to make this happen and we are entitled as a result to doubt the calibre of the members of the Scottish parliament.

Why did they not realise that the punishment for failing to say who you are cannot be one that depends on knowing who the perpetrator is? You can’t fine someone whose identity you don’t know. Land has the great advantage of being impossible to hide. The only meaningful punishment if a landowner won’t surface is confiscation of all or part of their land, temporarily or permanently.

The ultimate owner of Craiganour may have may good reasons for wishing to be anonymous, or indeed very bad ones. And he may or may not be legally obliged to register here in Scotland. The thing is that only he can know that due to the web of secrecy his advisors have crafted. And, as Joseph Pulitzer, the founder of the Pulitzer Prize had it “There is not a crime, there is not a dodge, there is not a trick, there is not a swindle, there is not a vice which does not live by secrecy.”

Scotland deserves better than its present landowners, civil service, members of parliament and especially its ministers. If the Cabinet Secretary for Land Reform is too fearful even to demand the names of Scotland’s absentee landlords, what chance to the people of Scotland have?