Land Reform and the Gentrification of Braemar

Regular readers will by now have (hopefully) picked up an odd and perplexing intellectual lacuna at the heart of the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill.

Ministers have got themselves into a spot of bother in attempting to justify why someone can be the second largest landowner in the country owning tens of thousands of hectares of land and yet, because no one parcel exceeds 1000 ha in extent, their landholding is outwith the scope of the Bill’s key provisions.

Here again is an exchange from the Stage One scrutiny. [1]

Michael Matheson:

If we get to the point where someone is the third-largest landowner in the country but does not have a land management plan to their name, while someone who happens to have one piece of land that is just over the threshold has to go to the extent of having a full land management plan, there will be a real inequity to that. That needs to be addressed.

Mairi Gougeon:

We would have to give greater thought to how that could be done and to the evidence base that we would use if that was to be the proposal.

The idea that concentrated landownership is only a problem if it directly impacts on an identified community flies in the face of 40 years of scholarship. My understanding is that the Scottish Land Commission only ever intended that this be a proxy for the impact that scale and concentration can have. Yet that relationship has never been tested by any empirical studies or evidence and has now found its way into a key piece of legislation as the supposed ‘evidence base” for the core proposals.

This blog highlights once again how the 1000 ha threshold chosen as the trigger for the various interventions in the Bill is arbitrary and fails to address other impacts on communities at a smaller scale. In my previous blog on this topic, I pointed out the impact that a 204h a landholding has historically had on a small village where the owners (who live in New Zealand) own almost all the land around it and all the streets within it. [2]

The example I want to highlight today concerns the village of Braemar in Aberdeenshire.

For those who know what has been happening here, this will not be entirely new. A very wealthy couple – Swiss art dealers, Iwan and Manuela Wirth – took on a lease of Invercauld House on Invercauld Estate. There was nothing unusual about that but, as Manuela said in an interview in The Gentlewoman in 2016,

“We have this house in Scotland, and we had no way to entertain our guests,” Manuela says. “We love a big table full of guests and family, but there is no possibility to invite these people to Scotland because there is not a single good restaurant or hotel near us. So when we heard about this hotel in Braemar which was for sale we thought, Why not?”

The Wirths acquired the Fife Arms Hotel in 2015 under their company Artfarm Property Ltd. They invested significant sums of money in the hotel and it is now a favoured destination of celebrities and royalty.

The Braemar Literary Festival will be held this coming weekend. It is billed as a “literary escape to the Highlands” – a neat summation of the distinctly metropolitan flavour of the event over the years.

But whilst private investment in the Fife Arms is to be welcomed (although much of the historic clientele of ordinary tourists, walkers and climbers have been replaced by a more monied class), the scale and pace of the property portfolio built up by the Wirths is staggering and has impacted on the local tourism industry.

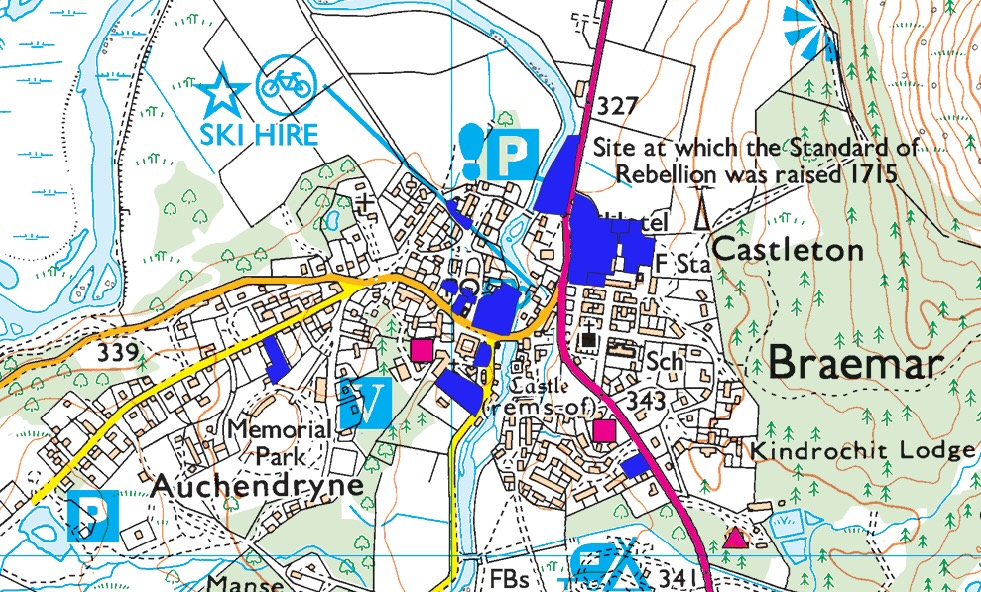

Following their acquisition of the Fife Arms in 2015, they have purchased a further eleven properties in Braemar and five in Ballater. These are illustrated on the map below in blue.

Prominent among them are the following.

The Invercauld Arms

The only other large hotel in town has now been closed and is to be covered into self-catering apartments with swimming pool, spa and gym facilities.

Schiehallion Guest House

A popular guesthouse in the village, it was bought in 2016 and is now closed.

Braemar Kirk

This Church of Scotland property was bought by Artfarm in May 2025.

Most of the remaining properties are domestic dwellings and former guesthouses which have been acquired as staff accommodation for the 110 or so staff employed in the Fife Arms and the 50 or so who will be employed in the self-catering apartments in the former Invercauld Hotel. [3]

I don’t know if this development of high end tourism is what the residents of Braemar want or need and it is not the purpose of this blog to debate the pros and cons of rural gentrification. However, the owners of these 16 properties, have been able to acquire them all with no questions asked. No doubt more homes will be bought in future to accommodate this expanding hospitality empire.

What is beyond question is that existing guesthouses have closed to make way for staff accommodation for the Fife Arms. This represents a form of creeping monopolisation of the hospitality offering in Braemar with the vast wealth of the Wirths being able to outbid anyone else who may want to provide holiday accommodation for other types of visitor to Braemar.

The extent of these holdings in Braemar extends to 3.7 ha but there is no doubt that the ownership of this extensive collection of properties is having and will have an impact on Braemar. Whether that impact is regarded as positive or negative or somewhere in between is irrelevant to the fact that there is an impact.

Should there be similar powers of intervention for Scottish Ministers in such cases where one owner buys up such an extensive property portfolio in a village comprising both main hotels and converts existing hospitality businesses into staff accommodation?

If not, why not?

NOTES

[1] Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee Official Report Cols 17-18 18 February 2025

[2] See blog of 3 July 2025.

[3] This document (5.2Mb pdf) submitted as part of the planning application to create staff accommodation in the former Inver Lodge Hotel sets out the logic of the property portfolio being assembled in Braemar.

Quite the takeover! Funnily enough though, I’m going up there this weekend to take part in this literary festival as an artist. We’re staying at a nearby guesthouse since everything in Braemar is booked solid and we definitely can’t afford the Fife Arms! Compared to other private estates, I suppose at least the festival brings people to Braemar, including considerably less wealthy people like myself. Art Farm says its aim is to integrate local arts, and the hotel shows a staggering amount of locally commissioned art – so it’s helpful on that level. What I did see there that saddened me, was that Downie’s Cottage has been bought by new private owners, who received funding from Historic Scotland to restore the house and the adjoining bothy. The bothy was made quite famous for the part it played in Nan Shepherd’s life. Anyone could stay in that bothy – in the spirit of bothies it was free. Now if you go anywhere near it, a pack of quite rabid, very noisy dogs springs out ready to attack. You can now stay at Downie’s Cottage if you pay ( it’s a guest house) but if you want to experience the place where Nan Shepherd unfailingly received a warm welcome and cup of tea from the owners, you’ll just have to read about it, because it’s firmly in the past. It’s not owned by Hauser and Wirth.

We live in Aberdeeen and have been visiting Breamar to walk and ski for about 50 years. Now we feel that Braemar no longer welcomes anyone who does not have a deep pocket to stay in the Fife or even visit the Fife bar, and are well aware of the decling number of guest houses and bed and breakfasts, being replaced by self catering accommodation which takes housing away from local residents. . I endorse Andy’s observation that the monied class are replacing people like us ; the traditional clientele . Art festivals etc are aimed at drawing wealthy visitors . I have long thought that Breamar has become Wirthtown,. Ballater is going the same way,

thanks Andy. I know one of those small hotel owners in Braemar… this is important, quite apart from the Land Act issue

This goes back to the original (albeit limited) research for the Land Commission in 2018 which indicated that CONCENTRATION OF OWNERSHIP is the real issue for communities in certain rural areas. By focussing on “1000 hectares” (or however many, the SG are missing the point and the Land Reform Bill may be more of a hassle than a help.

I’m a tour guide and hillwalker and have visited Braemar regularly over the years.

I think evaluating the impact and background is important and necessary to answer your question because it helps explain the why not.

I stayed at the Fife Arms 20 years ago. It was cheap but also the building was decaying. Cheap accommodation in an extensive historical building probably isn’t the best long run option, hence it was rundown. You need to bring in substantial income to restore and maintain such a building. The Wirths invested substantial amounts of money in not only restoring it but making it a sustainable business and building. To run that business of that size in hospitality they need high levels of staff and that has created a lot of new jobs in a rural area but they do need to be accommodated so that has created a housing problem. We have asked for job creation in rural areas for the social and economic benefits they bring to a local community, including repopulation, but they do need housing. The reason that the second hotel was sold was that it also run down and needed reinvestment. It’s purchase and space would relieve staff accommodation shortages and the intention is also to diversify the customer base. Yes the Wirths bought Braemar Kirk but the community bought St Margaret’s and use it as an arts venue.

I take a lot of international guests to the hotel and although they are well-off they are not particularly wealthy. They are people who have worked hard all their lives, saved their money and can now afford a nice holiday. They bring a lot of money into the economy. The hotel is very accessible for anybody using the Flying Stag, good quality food and drink from local suppliers at fair prices. From the few people I have sp0ken to in the village they don’t appear unhappy with the overall situation.

Is it gentrification? I don’t think so. It has always been a tourist village… that has been the reason for it existence. Has anybody been forced to move on? No. Is it assessable – more than ever. Camping and caravan site, youth hostel, lower prices self-catering units, bunkhouse, still independent B&Bs for those who want to stay in that business (despite over-legislation). Is there an active local community and a range of vibrant businesses? Yes.

On the point of B&Bs being bought in the village. I was B&B owner in a village just outside the Cairngorms which had many B&Bs. Since the Scottish Government applied draconian measures on B&Bs many owners have sold and new ones don’t want to buy. I’m not sure that the Wirths forced anybody out of the market, it was actually draconian legislation. B&Bs in the Highlands were great and what would have been unused bedroom capacity yet the owners still lived and were active in the local community and used other local businesses. These owner-occupied B&Bs have massively been replaced all over the Highlands by AirBnB self-catering apartments where the owner may live elsewhere, such as Edinburgh. This is really bad as although there is still basically the same number of beds for tourists yet much reduced accommodation for local residents.

So if the Wirths hadn’t bought the properties and occupied them with local staff who are there year round then who would have bought them? AirBnB hosts who are completely absent and never really invest anything in the local economy and create little in the way of jobs except some weekly Saturday cleaning jobs. From what I see at the Fife Arms the staff are happy, well-turned out , receive training, given opportunity to advance and provided with local accommodation.

Technically, the Scottish Ministers can intervene through the Monopolies and Mergers Commission. Though it’s exceedingly difficult to legislate when it comes to concentration. Also would it be ok if they had spread their staff accommodation purchases and say bought property in Blairgowrie and then bused or had the staff drive in. I would think that most would rather walk 5 mins around the corner than have a lengthy commute even if a free bus was provided.

Surely though if we want community empowerment then we want that intervention to be at grass roots not at Ministerial level by out of touch politicians in Edinburgh. Rather local decisions are made in the local community through a locally elected body. To my mind that would be the Community Council (and if they aren’t strong enough we should be strengthening and supporting them more to do this).

I think there is a limit to legislation and intervention (if only Parliamentary time and cost) and it should be concentrated at where our biggest problems lie. The likes of the Wirths and Povlsens investing time, energy and money aren’t really our greatest concerns and actually strive and meet many of our demands in terms of social and economic well-being, long-term investment, environmental considerations, working with other businesses; creating jobs directly and indirectly; community engagement. Public resources to achieve all these aims are limited and having diversification of types of ownership from state, community, private, charity is undoubtedly more beneficial in outcomes and innovation than having only one type.

May be the best place to focus Scottish Minister intervention in terms of rural Land Reform is on the sporting estate, where there is substantial evidence that outcomes are not at all in the public interest.

Alistair, good points and helpful context. For the record, I do not support the currentl Land Reform Bill as I think it is over bureaucratic and will achieve very little. I agree with your points about B&Bs. I opposed them ever being swept up in short-term let regulations but ScotGov thought otherwise. I also agree that the locus for at least some sort of avdance consultation over the developments that have happened should be the local community. The overall plans for such a significant intervention by the Wirths should be set out in full early on rather than emerge piece by piece as more and more property is acquired. That would allow for a fuller discussion of the potetntial impact. But that would be the type of public interest test which, although proposed by the Scottish Land Commission was rejected by Ministers.

The issue of mini-empires is becoming increasingly relevant across the Highlands. I’ve lived in the north-west for much of the last ten years. In that time, Povlsen has bought up most of the area around Tongue, a hedge fund billionnaire has bought Tanera Mor and is increasingly buying up land and businesses on mainland Coigach, and in Assynt, a wealthy southerner has bought the pie shop and cafe (Lochinver Larder), the neighbouring pub-restaurant (The Caberfeidh) and the Explorer’s Lodge in Inchnadamph. I’ve been told he’s also bought a few houses locally to house staff. What staff? The Explorer’s Lodge is still running but the pie shop and its accompanying cafe are open only under much-reduced hours and the Caberfeidh (to be blandly renamed ‘The Boathouse’), which has been a village pub for decades through several owners, has remained shut for years with no sign of the much-vaunted renovations. The website for the pie shop boasts that the expanded business will increase the school roll with a ‘raft of employment opportunities’. Instead, local premises appear to be being hoarded for private gain.

It’s just all so depressingly familiar.