The Vassalage of Langholm

Happy New Year!

The first blog of 2014 concerns the Kilngreen in Langholm and of how recent dealings raise concerns about the stewardship and governance of such an important area of community-owned land. It is a rather long blog but I hope that by reading it more folk are encouraged to research their collective land rights. I am grateful to Bill Telfer, a resident of Langholm, for research assistance.

In March 2013, I was invited to give a talk in the Crown Hotel, Langholm on land rights and burgh commons. In preparation for the talk, I undertook some quick research on the town’s common lands and quickly realised that I had a number of unanswered questions. After the talk, a number of us repaired to the bar and spent the rest of the evening discussing these. Prominent in our conversation was the legal geography of an area of land known as the Kilngreen and the role of the Duke of Buccleuch. Things became more interesting when we learned that some people had been advised not to attend my talk.

We decided to investigate matters further and what has emerged is a story of how powerful landed interests not only exerted considerable influence in towns like Langholm (which is the only enclave of land not owned by Buccleuch for many miles around) but continue today to exercise hegemonic influence on local political processes.

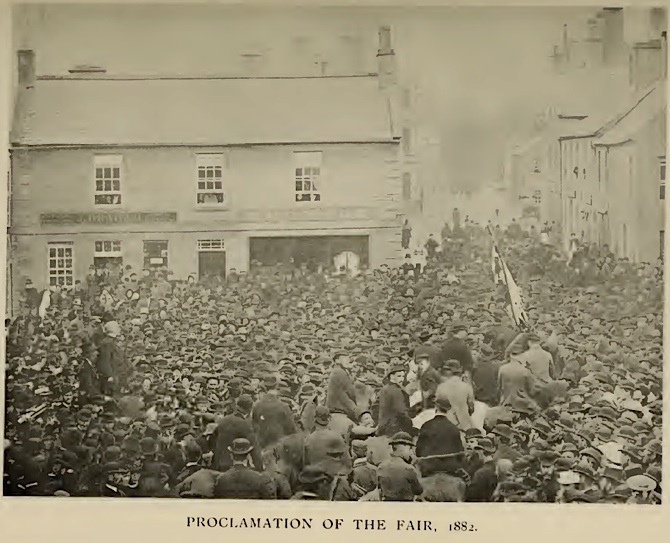

The Kilngreen is a seven acre parcel of common land to the north of Langholm. It was the site of the Langholm Summer or Lamb Fair held on the Kilngreen when townsfolk engaged in wrestling, horse-racing, greasy pole climbing and chasing the well-soaped pig (a traditional Borders games). The land forms part of the common lands of the town as narrated in the Proclamation of the summer fair.

Now, gentlemen, we are gaun frae the Toun,

And first of a, the ancient Kilngreen we gan roun;

It is an ancient place where clay is got,

And it belongs to us by Right and Lot;

And then from there the Lang-wood we gan thro,

Whar every ane may brackens cut and pou;

And last of a we to the Moss do steer,

To see gif a oor Marches they be clear;

And when unto the Castle Craigs we come,

A’ll cry the Langholm Fair and then we’ll beat the drum.

Langhom was created a Burgh of Barony in 1621 and from 1643 until 1892 the Duke of Buccleuch became feudal superior and exercised considerable power over the citizens. Notwithstanding the abolition of his hereditary jurisdiction in 1747 and the establishment of a police burgh in 1845, he continued to appoint a baillie and the magistrates of the burgh until 1892 when, under the Burgh Police Act, a Town Council was established. In the report of the inquiry into Municipal Corporations in Scotland of 1833, Langholm was stated to belong to that class of burgh “where the dependence upon the superior subsists unqualified and where the magistrates are appointed by him.”

The original 1621 Charter had been conferred by James VI to the Earl of Nithsdale, Lord Maxwell and in 1628 Maxwell entered into a feu-contract (a heritable lease at a fixed rent) with ten men from his own family in which he gifted each one merkland within the lands of Arkinholm for an annual feu-duty of 25 Merks each. This conveyance made these ten men Langholm’s first Burgesses. They were obliged by this contract, to build “Ilke ane of them a sufficient stone house on the fore street, builded with stone and lyme, of two houses height at the least, containing fourty foots within the walls of length, eighteen foot of breadth, twelve foot of height”. The building of these houses heralded the birth of the town of Langholm.

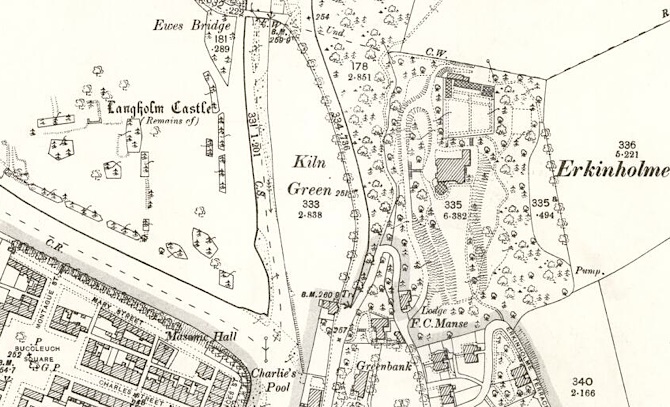

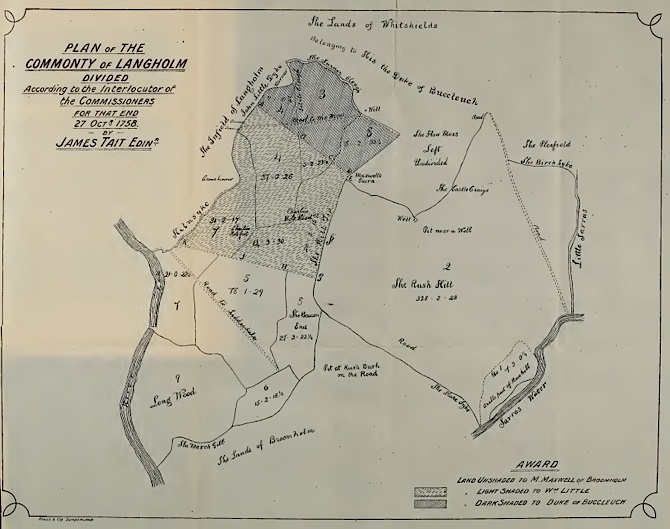

Meanwhile, the commonty of Langholm was situated to the east of the town and occupied most of the Whita Hill. By the mid 18th century disputes had arisen between owners of the Ten Merklands as to their rights over the commonty and in 1757 one of them, John Maxwell, raised an action against the other owners under the Division of Commonties Act 1695 to divide the common lands.

After due legal process, on 24 February 1759 the commonty was divided between John Maxwell of Broomholm, John Little and the Duke of Buccleuch. The court ruled that the common moss belonged inalienably to Langholm and was to be left undivided together with the loan, 20 feet wide, leading to the Moss. The tenants of the Ten Merklands and the burgesses of the town of Langholm possessed the right to lead stones and win fuel from the Common Moss and had also free access to it.

As a result of a separate inquiry (and central to our story), the court declared that the the Kilngreen, with rights of pasturage, “had belonged immemorially to the town of Langholm” and that “the limits and boundaries of these various Common lands should hereafter be as the Commission had awarded.”

The marches were described in sworn testimony to the Commissioners as follows,

“The march begins at the little Clinthead, where a pit was made, and from thence to another pit made at the corner of Johnathan Glendinning’s park nook, and from thence to another pit made at the side of a dyke at Janet Bell’s pathhead, and from thence along the dyke on the head of the Green Braes to a pit made at the lower ledge of the bridge, and along the said bridge to another pit made where the old watercourse was, and from thence to another pit near the foot of the mill dam, and from thence by pits made along the old watercourse, until it joins with the water of Esk at the foot of the old Castle garden, and down Esk till it join with the water of Ewes at the little Clinthead, where the said marches began.”

The award of the common moss and Kilngreen to the citizens of Langholm placed an obligation on the burgesses to ensure that the boundaries of the towns lands were clearly delineated and cairns were built and pits dug to mark them. It also led to the establishment of the common riding of the marches of Langholm, an annual custom that continues to this day as narrated in the proclamation above. It was decided to hold it on the day after the Langholm Summer Fair – at one time Scotland’s largest lamb sales and so began over 250 years of tradition. In 1979, the film-maker, Timothy Neat in collaboration with Hamish Henderson captured the essence of the occasion in his film “Tig, For the Morn’s the Fair Day”.

An excellent illustrated account of the 2013 Common Riding can be found on Tom Hutton’s Tootlepedal blog.

Langholm Common Riding Image: Tom Hutton

At first the annual inspection was carried out by individuals whose duty it was to “see gif a the marches they be clear” and to “report encroachments, clean out the pits, repair the beacons and generally protect the interests of the people”.

The first person to perform the inspection of the boundaries was “Bauldy” (Archibald) Beatty, the Town Drummer, who walked the marches and proclaimed the Fair at Langholm Mercat Cross for upwards half a century. In 1816 the marches were inspected on horseback for the first time and the Riding of the Common began. The first person to ride on horseback over the Marches was Archie Thomson, landlord of the Commercial Inn. In the previous year, Thomson, like “Bauldy” his predecessor, went over the boundaries on foot alone, but in 1816 he was accompanied by other townsmen – John Irving, of Langholm Mill and Frank Beatty, landlord of the Crown Inn being probably the most prominent. These local enthusiasts, sometimes referred to as the “Fathers of the Common Riding” were also responsible for introducing horse-racing, which took place on the Kilngreen until 1834, when the races and sports were transferred to the Castleholm across the river. (1)

Cumberland Wrestling at Langholm Common Riding Fair Games Image: Tom Hutton

****************

One might expect the legal record of ownership of the Kilngreen to reflect this clear and unambiguous history. However, what is revealed is something else entirely.

In 2009, a small building on the Kilngreen (the former tourist office) was sold to Buccleuch Estates Ltd. The deed transferring ownership of the tourist office from Dumfries and Galloway Council to Buccleuch Estates Ltd. (Land Certificate and Plan) reveals that the Kilngreen, far from having been owned by the town since time immemorial (as the court ruled in 1759) was actually gifted by the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry to the Provost, Magistrates and Councillors of the Burgh of Langholm in 1922 (we will return to this matter later).

Here is how the Eskdale & Liddesdale Advertiser reported the Langholm Town Council meeting on 1 May 1922.

LANGHOLM TOWN COUNCIL ORDINARY MEETING

Gift of the Kilngreen

Provost Cairns said he had been approached personally by the Duke of Buccleuch, and also Mr Milne Home, offering the Kilngreen to the town of Langholm, and he had been requested to approach the Council privately on the matter. Since then, he had received the following letter:

“His Grace has for some time past had under consideration the gifting of the Kiln Green to the Town Council. Owing to the uses to which the Kilngreen is put, and the control which it is essential to exercise over the travelling caravans which occupy the ground from time to time, the Town Council as a public authority, is already closely concerned.

The Kilngreen, as you may be aware, measures 2,838 acres, and what His Grace desires to convey to the Town Council is:

1. The whole title to the Kilngreen so far as His Grace has right thereto, with authority to levy and collect such dues as may be exigible from such subjects.

2. The area conveyed would be that shown upon the OS Sheet XLV.II, Dumfriesshire, Second Edition, 1899, as No.333, and measuring 2.838 acres, bounded on the West by the Ewes Water, and on the East partly by the Townhead Toll and the adjoining garden.

3. His Grace would reserve free and unrestricted access to the Toll House across and over the Kilngreen either for carts or foot passengers.

4. As it is His Grace’s desire that the ground should be maintained in all time coming as an open space for the use of the inhabitants of Langholm, the only reservation made in the gift is that no buildings of any description should be erected upon the ground without the consent of His Grace or his successors in title, and that the Town council should not have power to sell the ground or do any act which might divert it from the public use.

5. His Grace will grant a disposition to the Town Council, the draft of the disposition being submitted to them in the first place. This will enable the Council to complete their title in any way they may think best’’.

He had much pleasure in moving that the Council accept His Grace’s gift, and that they advise Mr Milne Home accordingly. Up to now there had been a certain amount of dual control over the Kilngreen which was not satisfactory, but now the inhabitants of Langholm would have full use of it as a recreation ground for all time coming, and he felt sure the town would greatly appreciate His Grace’s kindness. He had, therefore, much pleasure in formally moving the acceptance of His Grace’s generous gift, and that the best thanks of the Town Council and the inhabitants of Langholm to be conveyed to him.

Councillor E. Armstrong, in seconding, said he was sure the general public would greatly appreciate His Grace’s generosity. The Kilngreen had always been a touchy point as to ownership, but now that it had been handed over to the town they would say with all truth:

“It’s an ancient place where clay is got,

An’ it belangs to us by right and lot.”

But if the Kilngreen belonged to the people of Langholm from time immemorial, what on earth was the Duke doing gifting it to the Town Council and what was the Town Council up to in accepting it in such a sycophantic manner (His Grace, generosity, kindness etc.)? How in fact did the Duke himself come to own the Kilngreen? This latter question is answered in the 1922 deed.

The deed, recorded on 14 November 1922 opened,

“I, John Charles, Duke fo Buccleuch and Queensberry, K.T., heritable proprietor of the subjects hereinafter disponed, considering that as indicating my feelings of goodwill towards the inhabitants of the Burgh of Langholm, I am desirous of devoting to their perpetual use, benefit and enjoyment, the area or piece of ground hereinafter described as a pleasure or recreation ground, and I have the pleasure in making the underwritten perpetual grant or disposition of said subjects in favour of the Provost, Magistrates and Councillors of the said burgh of Langholm for the use, benefit and enjoyment of the inhabitants of the aid Burgh in all time to come…..”

“..which area or piece of ground is part of ALL and HAILL the lands of Langholm and others in the County of Dumfries particularly described in the Notarial Instrument in my favour recorded at length in the Division of the General Register of Sasines applicable to the County of Dumfries……the twenty second day of June, Nineteen hundred and fifteen.”

A Notarial Instrument is a declaration of facts drawn up by a Notary Public. The basis upon which the Duke of Buccleuch claimed to be the owner of the Kilngreen rested upon a 1915 re-statement of the Barony of Langholm charter granted to the Earl of Buccleuch in 1643 which includes

“the town and lands of Cannoby, the lands of Toddscluegh and Lambscleugh, the west side of the lands of Rowanburn, the lands of Newtown, Baitbank, the lands of Weitlieholm, lands of Archerlie, lands of Lochbushill……”

and so on for over 32 pages. With regard to Langholm, the deed narrates,

“..the lands of Langholm, with Fortalices, Manor Place, Milns, Fishings and Pendicles thereof called Holmhead, and Burgh of Barony of Langholm, with the weekly Market and free Fairs thereof, with customs, liberties, &c. thereof….”

So the Duke of Buccleuch was asserting that, in fact, he had owned the Kilngreen since 1643. How can this claim be reconciled with the court declaration of 1759? One clue is provided by a court case in 1816 – a significant year in the history of the Kilngreen and the common riding when the marches were inspected on horseback for the first time.

Local historian, the late David Beattie, recounted the case in the Eskdale and Liddlesdale Advertiser.

Court Battle Over Kilngreen – Year 1816

A lot of interest has been placed recently in the ownership of the Kilngreen and, as all Langholmites know, the battle for its ownership has been a long and prolonged one. We thought that the following story of a court case in 1816 would be of interest to locals.

In Dumfries Sheriff Court before Sir Thomas Kirkpatrick, William Beattie, George Graham, Archie Thomson, and David Hounam were charged with “mobbing and rioting on Friday night, the 15th day of December, 1816”. The libel set forth that the four defendants entered an enclosed piece of ground on The Kilngreen, belonging to Archibald Scott, writer, rooting up and carrying off a number of young trees. These trees were taken to one of the inns in Langholm by Beattie, who exhibited the trophies.

On the following day, the services were obtained of the “common drummer of the village of Langholm”, and a procession was organised, many of those who took part being armed with spades and long poles. “This irresponsible regiment” says the report “was led by William Beattie, who assumed command, and the second visit was paid to the garden enclosure, when the remaining young trees were pulled up, fastened to the ends of poles, and carried through the village in triumph”.

As can well be imagined, this sanguine battle for what was considered the town’s rights, now being fought out in this court at Dumfries, created considerable interest and lasted three days.

The prosecution claimed that the ground in question was the property of the Duke of Buccleuch who granted the present owner permission to enclose it in the year 1812. On the strength of this sanction, Mr. Scott carried out the enclosure and several trees were planted. Two years later he went further. Scott began cutting a trench for the foundation of a wall outside the line of trees which was assumed to be the new boundary. It was then that the turmoil began. Public feeling ran high. Such unwarranted action was regarded as a flagrant encroachment on the Commonty of the Kilngreen, consequently the wall was never built. Nevertheless, a good deal of indignation kept brewing until the storm broke which had its sequel in Dumfries Court of Law.

It was reckoned a glorious victory by the townfolk, who stuck to the letter of the Proclamation “The Kilngreen”, they said “is an ancient place where clay is got, An’ it belongs tae us by richt an’ lot”.

In their defence it was claimed that the inhabitants of Langholm had been in the practice of riding the marches of the different commonties once a year from time immemorial and contended that they were entitled in the exercise of this right to remove the trees planted by the pursuer.

After prolonged argument and debates, the Sheriff found the defendants liable for the damage done and the expenses of the action. The four men implicated were ordered to pay £20 each, which they did with the exception of David Hounam who indignantly refused to pay one penny. He was sent to Dumfries Jail where the refractory weaver paid the penalty (but not in hard cash) for his alleged misdeeds.

Billy Young, in his 2004 book “A Spot Supremely Blest” treats these events as a bit of a joke. But this is 1816. Here were some young men whose fathers no doubt had been alive when Langholm’s common lands were affirmed by the highest court in the land in 1759. One of the defendants was none other than Archie Thomson – the first person to ride the marches of Langholm’s commons that year. As the landlord of the Commercial Inn he would probably have been someone of standing in the community. Seeing evidence of appropriation of the Kilngreen, Thomson and his colleagues did their duty in defending the town’s land from encroachmant.

The so-called ‘’mobbing and rioting’’ is known about in Langholm but is given a rather low profile. The direct action of these Langholm men who marched up the High Street to the Kilngreen carrying spades, with the Town Drummer to the fore to prevent the attempted enclosure, then uprooting the young trees and tying them to the end of long poles and returning down the street were engaged in as militant a demonstration of public feelings as one can imagine. Indeed it is out of this event that the Common Riding as an event took shape, starting with militant direct action and still containing much of that spirit.

Aside from the horses, he main component of the Common Riding is the flute band and its drum (descendents of the role played by the Town Drummer) together with the foot procession. The Common Riding emblems ( the spade, the thistle, the barley bannock/saut herring, the floral crown) are brandished triumphantly on poles.

Langholm Common Riding Emblems – the spade, the barley-bannock, the crown & the thistle 1957.

Source: Langholm Archive George Irving collection.

In 1792, Thomas Muir had established the Friends of the People Society and four years later John Baird and Thomas Hardie led the Radical War of 1820. This was a time of revolutionary fervour. A Tree of Liberty had been planted in Langholm’s Market Place in the 1790’s. The reaction of Thomson and his friends to the encroachment and the subsequent attitude of the Sheriff of Dumfries, Sir Thomas Kirkpatrick can plausibly be viewed in this light.

The Duke of Buccleuch remember continued to appoint the magistrates of the burgh until 1892 and they no doubt would have felt obliged to pursue a prosecution. The consequence of their failure to defend the interests of their townspeople was that their successors (Provost Cairns and Councillor Armstrong) fell over themselves a little over 100 years later in 1922 to prostrate themselves before “His Grace’s” generosity and kindness in gifting them land they already owned.

Langholm Common Riding. Crossing the Ewe from the Kilngreen to the Castleholm. Image: Tom Hutton

It is unclear what motivated the Duke to gift the land in 1922. It is evident that he wanted some solution to the issue of travelling people. It is also probable that he and perhaps the Town Council realised that, although the Kilngreen was owned by the town, there was in fact no recorded title in the Register of Sasines. Quite why this was apparently never done between 1759 and the 1816 incident remains unclear but as feudal superior, Buccleuch was the obvious person to rectify the omission…….which brings us to back to the sale of the tourist office.

****************

In the 1922 deed of gift, the Duke of Buccleuch stipulated that the Kilngreen was “for the use, benefit and enjoyment of the inhabitants of the aid Burgh in all time to come”. He also imposed a condition that the land could not be sold without his consent. (2)

In 1999 Dumfries and Galloway Tourist Board vacated the tourist office and it lay vacant for a decade before the Council’s Resources Committe met in April 2009 to conclude plans for its disposal. The Council wanted to sell the building as it was surplus to their requirements (though note that the beneficial owners are the people of Langholm the decision was never considered by any common good fund committee). Due to the restriction on sale, Council officials had approached Buccleuch Estates Ltd. for a Minute of Waiver – a legal agreement to waive the condition. Buccleuch refused on the grounds that a sale on the open market “would not be consistent with the intentions of the Buccleuch family when they gifted Kilngreen to the inhabitants of the Burgh iof Langholm”.

Buccleuch did indicate, however, that it would be interested in “buying this property back from the council with the intention of putting it to some form of community use, thus being consistent with the family’s original intention”. The proposal was to lease the building to the Langholm Initiative as a Moorland Education Centre.

The Council agreed to this. The purchase price remained the “open market value” but by now the “market” had been reduced to one party – Buccleuch Estates Ltd. – and a price of £500 was agreed. The sale went through in September 2009 (Land Certificate and Plan).

As the Resources Committee report makes clear, one of the reasons that the Council wanted to dispose of the building was that it was in a dilapidated state of repair and represented an ongoing liability. But that summer a TV company arrived in Langholm and renovated the building!

The renovated former tourist office sold to Buccleuch Estates Ltd. for £500.

****************

So, at the end of this long tale, the Buccleuch family gifted land that was never theirs to gift in the first place, imposed conditions that tied the hands of the Burgh and which, almost a century later, the Buccleuch family exploited to refuse a waiver that depressed the price that allowed them to buy it back (having been given a makeover by TV money and local voluntary effort) at a fraction of its market value thus depriving the common good fund of a much needed capital receipt. All the while, the people of Langholm have been let down by a lack of transparency as to the land’s true ownership and by a Council that, when I asked them in 2009, reported that there were no common good assets in Langholm.

All of which is made the more galling when there were alternative courses of action available to the council.

Under Section 20 of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003, an owner of land over which there is a title condition or restriction may, after 100 years has elapsed since the burden was imposed, register a notice of termination of the burden. Thus Dumfries and Galloway Council could have called Buccleuch’s bluff and threatened to wait until 22 November 2022 and be shot of all the conditions that curtailed its freedom of action unless the waiver was granted. Until then it could have either demolished the building ot leased the site directly to the Langholm Initiative on a full repairing lease. Such a lease, of course, would require the consent of Buccleuch Estates but since they presumably consented to the Tourist Board’s occupation of the building, could not reasonably refuse a new lease. Had they done so, the Council should have gone straight to the Lands Tribunal to apply for an order to permit the lease to go ahead.

The irony of all of this is that for £500 the residents of Langholm could easily have bought back their own common good land, though they would have been quite rightly indignant at having to do so given that a little over 250 years ago the Court of Session ruled that it already belonged to them.

For that 250 years, the residents of Langholm have for a variety of reasons, been ill-served by feudal patronage, corrupt and undemocratic governance, and the inability to take decisions by themselves in their own interests over land that belongs to them. That this state of affairs has persisted this long and over a decade since the advent of devolution is a powerful reminder of how little attention has been paid to land and governance matters within Scotland.

When, in March last year I sat in the bar of the Crown Hotel, I knew nothing of its former landlord, Frank Beatty and the mobbing a rioting of which he had been found guilty in defence of the town’s land rights. On the wall of the hotel lobby is a poster narrating the history of the common riding. Those who take an interest in such matters know this history well. Over the river, in the new Langholm, is a town built on Buccluech land where “His Grace’s” interests still hold sway. Feudal hegemony is alive and well in Langholm.

Perhaps it is time for some more mobbing and rioting.

SOURCES & NOTES

Much of the history of the KIlngreen is covered by John and Robert Hyslop’s classic book Langholm As It Was published in 1912 by Hills and Company, Sunderland.

(1) The move across the water to land owned by the Duke of Buccleuch (Castleholm) is reflected in the rest of the Fair Proclamation as cited on Tom Hutton’s blog here that the Fair is to be held upon “hus Grace the Duke of Buccleuch’s Merk Lands.”

This is to give notice that there is a muckle Fair to be hadden in the muckle Toun o’ the Langholm on the 15th day of July, auld style, upon his Grace the Duke of Buccleuch’s Merk Lands, for the space of eight days and upwards; and a’ land-loupers, and dub-scoupers, and gae-by-the-gate swingers, that come to breed hurdums or durdums, huliments or buliments, hagglements or bragglements, or to molest this public Fair,they shall be ta’en by order of the Bailey and Toun Cooncil, and their lugs be nailed to the tron wi’ a twalpenny nail, and they shall sit doun on their bare knees and pray seven times for the King and thrice for the Muckle Laird o’ Ralton, and pay a groat tae me, Jamie Ferguson, Baillie o’ the aforesaid Manor, and I’ll away hame and hae a Bannock and a saut herring tae ma denner by way o’ auld style.

(2) The deed also states that “ nor shall my said disponees be entitled to erect buildings on the said subjects without the written consent of me or my successors, or to sell, dispone, or otherwise alienate, or to grant leases other than for pasturage of the said subjects, or any part thereof, or to do any other act by which the inhabitants of Langholm might be deprived of the use or enjoyment of said subjects.”

I have seen a case like this before where land is claimed by several people and each believes he has good title to it. It’s come about because past ownership has been forgotten and new ownership assumed; no one is deliberately doing anything wrong it’s just the cock-up factor running rampant and it isn’t easy to sort out.

I suspect that the duke of buccleuch “gifted” the kilngreen to the burgh in 1922 as an easy way out of a tricky situation before he was rumbled by the locals.

1922 was a worrying time for the aristocracy as they lived in peril of communist uprisings like happened in glasgow and in europe.. The first labour govt had just been elected, and maybe the duke wished to improve his image locally in case of trouble.

Picture the scene ;

Duke; What can we give away to improve our image among the proleteriat?

Factor; Give them the kilngreen, they own it anyway but dont know it.

Duke; What a jolly wheeze, draw up the papers straight away. Jeeves, crack open the champers. A toast; revolution is averted, and cheaply at that.

Long live the aristocracy!

Kilwinning Abbey lands were dispersed to Hamilton family and others by dubious legal means throughout the 16th Century.

The Montgomerie family, Earls of Eglinton, also acquired rights over much of Cunninghame in North Ayrshire.

Much more research into original charters is required to establish the truth about land ownership and abuse of the Common Good Assets by Burghs and Councils as well as Landowners.

HI Ian,

What sources do you know of for the land around North Ayrshire. I’m an Irvine local so would be interested in doing some digging. I think there’s a real need to tell the story of what has happened to the Common Good Assets of the town (as Andy has just done for Langholm) as a way of engaging people in and informing the current (mis)management.

Are you in Ayrshire yourself? Interested in starting a working group on the issues?

Finally got round to following up some leads which Andy gave me at a while back at Wigtown book festival and put in a request to the Registers of Scotland yesterday for some info on Boggar Corn Exchange and several other sites in Biggar which I think are likely either Common Good or Commonity. South Lanarkshire Council say that there are no Common Good Assets in belong to the Burgh of Biggar (which seems rather odd as we have a Common Good fund!)- will be interesting to see what comes back! I think in this case they may be misappropriation by the council rather than aristocracy, but nevertheless.

What an excellent exposition.

What about the Common Moss at Langholm, which is continuous with, and now somehow part of, the Langholm grouse moor (Owner Buccleuch Estates)? Like the Kilngreen, it was subject to a 1759 ruling over the division of the commonty on Whita Hill, which placed the common moss as belonging to the people of Langholm. The moss was left undivided.

Why didn’t either of these rulings get into the Register of Sasines?

You are quite correct. The Common Moss was awarded to the burgh of Langholm. I don’t know if a title was ever recorded or not. If not, it should be. As I point out, as of 31 December 2012, Dumfries & Galloway Council reported no land or property held in the Langholm Common Good Fund. This is clearly an error. As the statutory successor to Langholm Town Council, all of the land belonging to Langholm should be properly recorded both in the Registers of Scotland and within the records of the Council. More work to do clearly!

Wigtown Book Festival…

… I was brought up on the farm of Kirvennie, within the Royal Burgh of Wigtown, to which Janet & Andy refer….what about the Common Moss and right to dig peat as fuel, rashes to protect the hay/ cornstacks etc, Common Good Fund, Riding of the Marches etc…?

I’m delighted at having been able to provide Andy with the researches relating to Buccleuch’s ‘’legal theft’’ of our Common Land, and how the facts have tended get glossed over, even suppressed. 1) the Duke’s ”gracious granting” of the Kilngreen to a sycophantic Town Council in 1922 even though this land has actually belonged to us from time immemorial! 2) the 1816 attempted appropriation of a section of the Kilngreen leading to ‘’the Battle of the Kilngreen’’ as described by the late David J Beattie. I’ve often felt that Langholm people should be more aware of this aspect of our heritage and appreciate that when we witness (or participate in) the procession on the Common Riding Day it as an event that developed out of the radical militant action of these men marching up the street ”armed with spades and poles… uprooting young trees and fastening them to long poles…..triumphantly brandished …..’’. Look at that photo in Andy’s blog, and others that can be seen in the Langholm Archives -how the emblems are carried. This procession resembles a political ”demonstration”! But in official descriptions of the Common Riding this aspect is played down, almost a cover-up! It can be said that although now ceremonial, the town every year is re-enacting that 1816 radical action.

This year let us maintain that spirit of radicalism when we come to vote yes on 18th September for a more democratic, better Nation.

This is just a tiny example of the mass theft of land carried out by the aristocracy over the centuries.

It may be “legalised” in the register of sassines, but it is theft nonetheless.

Then the tenant farmers improved, drained and cleared the land, and the lairds stole that too.

So the Council was ‘gifted’ land by a Duke that didn’t own it, the Council then sold this land back to the Duke’s estate. However as the Duke never owned the land in the first place he surely couldn’t actually sell it. Therefore the Council never legally owned it and therefore it has not actually been sold back to the Duke’s estate.

This land still belongs to the common good.

This is not the only case I have heard if Council’s selling or trying to sell land they do not own.

Well, the Duke claimed to own it in 1922 on basis of a 1915 title recorded in Register of Sasines. Scots law is strict on ownership – a recorded deed is a pre-requisite for any claim of ownership and it appears that no title was ever recorded following the confirmation in 1759 that the land belonged to the town.

When Andy asked D&G council about Langholm common good assets he was told there were none.

I submitted an FoI request to the council in 2010.

The information given was that the Langholm Common Good Fund had no ‘cash’ so are they justified in saying there cannot be a Langholm Common Good Fund? However they admit that the town does have Common Good Assets, see details below. Meanwhile I have come across this quote in course some online discussions with various people but am not sure of its significance for Langholm:

” The distinction that has been drawn between what has been deemed to be ‘Council Assets’ as opposed to ‘Common Good Assets’ of former Burgh property, is a spurious one, unless it can be demonstrated that the asset was acquired in the circumstances defined by Lord Wark in the Inner House, which we now quote:

common good property is… “all property of a royal burgh or a burgh or barony not acquired under statutory powers or held under special trusts” … Magistrates of Banff v Ruthin Castle Ltd 1944 SC 36 at p 60.

Lord Wark’s judgement above was confirmed and endorsed in another Inner House case: Wilson and Others v Inverclyde Council, Case No A2312/99 dated 20 February 2003:

Lord Osborne at para 24 & 33;

Lord Drummond Young at para 5;

Lord Coulsfield at para 4.

An Inner House ruling by a bench consisting of three judges has therefore recently, undeniably and irrefutably, stated the law pertaining to the Common Good as it stands at present. The law is therefore perfectly clear.”

Be that as it may the FoI response did provided some interesting information about Langholm’s Common Good Assets.

Quote:

‘’…I would point out to you that there are asset valuations enclosed – these are the value of the asset to the Council in their existing use, they are for Capital Accounting purposes and should not be used for any other purpose – the Council is not required to value “Community assets”

As the Langholm Common Good Fund has no ‘cash’, there is no specific body set up to administer the assets. However in the absence of a specific group set up by the Council – it is the Council which takes on this role. As such we maintain the assets……..

….. You should be aware that the Council holds the copyright for the material provided and it may be reproduced free of charge in any format or media without requiring specific permission. This is subject to the material not being used in a derogatory manner or in a misleading context. The source of the material must be acknowledged as Dumfries and Galloway Council and the title of the document must be included when being reproduced as part of another publication or service.’’

A document provided (titled LANGHOLM COMMON GOOD – ASSETS) gave this information:

”No cash assets remain in the Langholm Common Good Fund. A minute of a meeting of the ‘Provost, Magistrates and Councillors of the Burgh of Langholm dated 10 April 1975 agreed to disperse remaining funds of £319 to 3 local groups.

Physical assets of the Langholm Common Good Fund:-

The Kilngreen, Langholm

The Town Hall, Langholm

The Library Site, Langholm

Garden Ground at Rosevale Street, Langholm

Eldingholm Public Park, Langholm

The former Tourist Information Office was sold in September 2009.”

Then an Excel document entitled ‘’ langholm cg 10’’ is a table headed Property Search Results provides some Values of these Assets:

-Under Property Type the Eldingholm Public Park a Community Asset with an Asset Value of £0.

-The Playpark and Public Gardens Rosevale Street Langholm DG13015 is a Community Asset with an Asset Value of £0.

-Langholm Town Hall, market place, Langholm DG130JQ is a property type of Office, Hall, and Library with an Asset Value of £597,000.

-Car Park, Kilngreen Townhead, Langholm DG13 0EP under Property Type is a Car Park an Asset Value of £311,000.

-Public Toilets, Kilngreen Car Park is a Public Toilet with Asset Value of £93,000.

Finally,

-Public Toilets, Mrket Place, Langholm Dg13 0JQ is a Public Toilet with an Asset Value of £0 and ‘’inside the Town Hall’’.

My FOI submission had also asked if there were any other burghs in D&G having Common Good funds. The information provided was that there are 11 old Burgh Towns in D&G having CG funds I.e Common Good Funds are held for the benefit of residents of the former Burghs of Kirkcudbright, Castle Douglas, Gatehouse of Fleet, Annan, Lochmaben, Lockerbie, Stranraer, Whithorn, Wigtown, Sanquhar and Dumfries.

I have nothing to say about these towns but if anyone wants to know what was provided about their CGF’s with the FoI response I can forward it to you (provided you’re not going to be ‘’derogatory’’ about the information)!

I do know that there are other towns in D&G which have no CG funds, probably for similar reasons (negligence of Langholm Town Council in 1974 for throwing away the town’s CG fund). Could we ask today – why cant we re-establish the Common Good Fund, given the value of these properties/assets adding up to millions? Also we should beware of the fact that the council has a policy for ‘’integrating’’ all the council the services in the town, to put them under one roof ie, council office, registration, local library, currently accommodated in separate buildings, so there could be a danger of altering, closing or selling, an old building which is a clear asset to, the old Town Hall which is very much a Common Good Asset.

Is everyone awarre that the SG is canvassing opinion on the proposed Community Empowerment Bill?

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2013/11/5740

The proposals are patchy but are heavily weighted in favour of LAs and will give them almost ‘carte blanche’ in administering CGFs.

You have until the 24th Jan to comment.

I live in Kilwinning and am a native of Ardrossan, now retired I’ve joined Kilwinning Heritage and post information on the Threetowners forum on local history matters and in particular the Missing Common Good Assets of Ardrossan, Saltcoats and Stevenston. There are other interested parties on the forum with experience and expertise on Local Government matters. I’m creating a list of possible Common Good Assets and Funds in North Ayrshire and hope to identify their status from sources other than the NAC who have shown little information in their accounts. Since the creation of IDC and CDC and NAC Irvine to Largs Common Good matters are linked with the 3 Towns + Kilwinning.