The Scotland Bill & the Crown Estate (2)

The provisions in the Scotland Bill for the devolution of the management of the Crown Estate in Scotland are complex and unclear (see previous blog for background).

The provisions in the Scotland Bill for the devolution of the management of the Crown Estate in Scotland are complex and unclear (see previous blog for background).

Last week, the Scottish Parliament’s Rural Affairs, Climate Change and Environment Committee (RACCE) heard evidence from representatives of the Crown Estate Commissioners (CEC) and some significant points came up. (1) Here are my latest thoughts on why Clause 31 of the Scotland Bill fails to implement the Smith Agreement on this topic.

In 1999, Crown property rights were devolved under the Scotland Act 1998. However, the management and revenues were reserved and remained under the control of the CEC. The Smith Agreement is to devolve the management and the revenues. To achieve this is straightforward. The two reservations (of management and of revenues) in Schedule 5 of the 1998 Act need to be removed.

Once these removals take effect, the responsibility for the management and revenues of the Scottish Crown property, rights and interests that currently make up the Crown Estate in Scotland would fall by default to the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government. While Scottish Ministers would need to put in place the necessary administrative arrangements to deal with these new responsibilities, there is no need for any further legislation. Once this has happened, the Scottish Parliament can begin the process of decentralisation (to which all political parties are committed) and some of which will require legislation to put into effect.

In contrast with that approach, the Scotland Bill provides for a “transfer scheme” whereby functions of the CEC may be transferred to a transferee in Scotland and continue to be governed by a modified Crown Estate Act 1961, until such time as the Scottish Parliament determines otherwise. One of those giving evidence to RACCE was Rob Booth, the Head of Legal at the CEC. He said, in response to a question that,

“The position after the transfer date will be that the Crown Estate Act 1961 will be applied as a fallback, to fill a potential vacuum. At the transfer date, if no Scottish legislation has been brought forward to set up the structure to take on the new role, a modified version of the 1961 act will be applied as an interim measure until Scotland has had an opportunity to pass that legislation.

In my reading of the Scotland Bill, it is not anticipated that there will be an on-going application of those 1961 act principles to management in Scotland. After the transfer date, as things stand, the 1961 act will apply only to the Crown estate in the rest of the UK, so Scotland will have freedom as far that particular aspect is concerned.” (2)

In other words, the Scotland Bill would remove the Schedule 5 reservation on management (we will deal with revenues shortly) but rather than keeping things straightforward as outlined above, Clause 31 would put in place a Treasury transfer scheme which binds nominated transferees into a legal framework governed by the Crown Estate Act and which needs to be undone by the Scottish Parliament if and when it wishes to do so in relation to the various Crown property rights and interests involved.

It remains unclear why this added complexity is necessary. Four other aspects remain unclear.

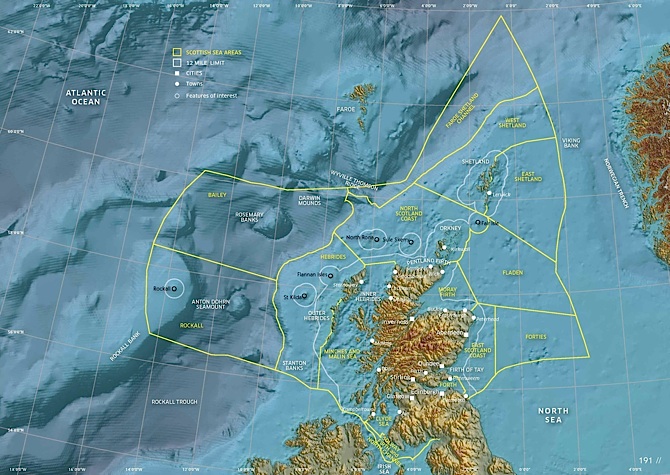

The first is the question of the revenues. It is now clear that the Scotland Bill will not devolve the revenues. Instead, it amends the Civil List Act to the effect that all revenues will be paid to the Scottish Consolidated Fund. The reservation in Schedule 5 remains in place, however, and so it will be incompetent for the Scottish Parliament to make any change to this arrangement. This, in effect, makes decentralisation very problematic. The promise that the First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon made in Orkney two weeks ago, that “coastal and island councils will benefit from 100 per cent of the net revenue generated in their area from activities within 12 miles of the shore” is made rather difficult if all of the revenue has, by law, to flow to the Scottish Consolidated Fund. (3)

The second matter relates to the idea that, after devolution, the CEC will continue to be able to acquire land in Scotland. This is legally incompetent. The CEC does not acquire land or property interest in its own behalf but does so on behalf of the Crown. Constitutionally and legally, the Crown is a distinct entity in Scotland from the rest of the UK. Were the CEC to acquire, say a shopping centre in Scotland in 5 years time, it would be owned by the Crown in Scots law but acquired from revenue derived from the English Crown. Constitutional experts will be better placed to address this question than I but I do not think this is constitutionally possible.

Thirdly, the Scotland Bill at Clause 31(10) stipulates that any management of Crown property in Scotland shall maintain the property, rights and interests as “an estate in land”. Rob Booth described this as “a fundamental founding principle of the Crown Estate”. (4) But after devolution there will be no Crown Estate in Scotland (the term will only apply outside Scotland). Crown property rights have been devolved since 1999 and this constraint represents a reversal of the current competence of the Scottish Parliament for no good reason.

Finally, the Fort Kinnaird retail park in the east of Edinburgh will not be included in the devolved settlement. Rob Booth explained this in the following terms.

“As a lawyer reading the Smith proposals, I can see that Smith talked about Crown Estate economic assets in Scotland being devolved to Scottish ministers. There is a statutory definition in section 1(1) of the Crown Estate Act 1961 of what the Crown estate is, which is those assets that are managed by the Crown Estate Commissioners. Fort Kinnaird undoubtedly is an economic asset in Scotland, but we do not manage it. The underlying asset is not owned by the Crown; therefore, to my mind as a lawyer, it does not fit the definition of a Crown Estate economic asset in Scotland as described by the Smith report.” (5)

Fort Kinnaird is owned by a partnership – The Gibraltar Limited Partnership. In Scots law a partnership is a legal entity and may own property in its own right. The Gibraltar Partnership, however, is governed by English law, specifically the Limited Partnership Act of 1907. Such partnerships are not legal entities and it is the partners that are the legal owners of the property. There are two partners in the Partnership – the CEC on behalf of the Crown and the Hercules Unit Trust. Since Fort Kinnaird is in Scotland, the interest that the CEC has is an interest owned by the Scottish Crown. (6)

Rob Booth’s explanation is unconvincing, disingenuous and wrong. The underlying asset (the interest) is owned by the Crown, the CEC manages that interest, and it does therefore form part of the Crown Estate.

To conclude, the Scotland Bill does not implement the Smith Agreement. Instead it creates a complex and incoherent muddle where there should, instead, be clarity and simplicity. The Scotland Bill is about devolving further powers to the Scottish Parliament. That is achieved by removing the two key reservations. That’s all, in essence, that it needs to do (although there are minor consequential amendments) and it doesn’t even achieve that. In the Committee stage of the Bill on 29 June 2015, MPs should ensure that it does.

NOTES

(1) Official Report here

(2) Official Report Cols 12-13

(3) See Shetland Times, 21 June 2015

(4) Official Report Col 14

(5) Official Report Col 6

(6) See here for Companies House filing history on the Partnership

Would you have any objection to me sending a copy of this to Graham Smith the CEO of Republic as it raises some very interesting constitutional points? You will gather that I am a member of Republic.

Andrew

Feel free to do so.

I did wonder where we stood on this. Thank you for the clarification.

Yes, a clear and simple choice in terms of the modifications you suggest. In fact as Monty Python would say ‘it’s the bleedin obvious’. Now, how will the SNP government avoid it this time?

Oh Gie’s peace, Ron! Let’s focus on getting this right rather than settling old scores.

Graeme Purves:

are you a Civil Servant working for the SNP government or a party hack? The SNP has neither done anything wrong or right on most aspects of the land tenure-land use issue, as basically it has done nothing yet. Here is a chance to get a simple thing right, but their track record is not encouraging.

I’m neither. I have retired from the civil service and I’m a member of the SNP. I don’t think that makes me a “party hack”.

I’m sure a great many people in the SNP support the approach to the legislation Andy proposes. Divisive point-scoring is not going to help us achieve a satisfactory outcome.

I spent 25 years in the SNP and was a member of their Land Commission that reported to party approval in 1997. I have yet to see a satisfactory outcome from the SNP on land reform. The pressure has to be kept up on them. They have to justify their position, not wallow in it.

That was 1997. This is now.

same people, same outlook, can’t even handle the concept of a national park being owned by the nation, same track record of inaction and abrogation.

Andy

Ten lines from below: what is meant by the Scottish Crown?

Scottish Crown means the Crown in Scotland – a distinct legal and constitutional entity from that in England.

Andy

Please can you explain the significance of what you have written:

Since Fort Kinnaird is in Scotland, the interest that the CEC has is an interest owned by the Scottish Crown. (6)

Do you have a view as to why they have made it so complicated?

My take is that it’s been deliberately complicated to allow Westminster to keep their sticky fingers in the pie and prevent Holyrood from being able to manage it effectively.

Cynical, Moi!

It looks like the latest land reform bill is yet another lawyers feast.

Tenants should have ARTB now for their house and buildings and 50 acres. Those derelict homes on islay would have still been happy family homes if the tenants could have bought them.

Johnston, margadale and astor are the greatest advert yet for ARTB.

Hilarious fopa from margadale about a son not necessarily having the skills of his father!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Andy, you may know more about English partnership law than the Crown Estate’s head of legal but accusing him of being disingenuous is out of order.

But aside from the fact you’ve changed your tune from what you told the SAC in 2011 (Fort Kinnaird “not technically owned by the Crown Estate Commissioners but is held by some investment vehicle. You can just forget about that.”) it’s actually you who’s wrong about partnership property.

Title to an English firm’s land is held by trustees (often, but not necessarily, the partners) who hold it in trust for the partnership purposes. Don’t take my word for this – see sections 20(1) & (2) of the Partnership Act 1890 and para 5.22 of the Joint Law Commission Report http://tinyurl.com/o232o6y What this means in practice was summarised in a 1997 Court of Appeal case called Popat v Shonchhatra as follows:

“While each partner has a proprietary interest in each and every asset, he has no entitlement to any specific asset and, in consequence, no right, without the consent of the other partners or partner, to require the whole or even a share of any particular asset to be vested in him. … It is only at that stage [division of partnership assets upon dissolution of the firm] that a partner can accurately be said to be entitled to a share of anything, which, in the absence of agreements to the contrary, will be a share of cash.”

That is explicit judicial authority that your assertions “Since Fort Kinnaird is in Scotland, the interest that the CEC has is an interest owned by the Scottish Crown. … The underlying asset (the interest) is owned by the Crown” is wrong. (And if, as I understand from the SAC Crown Estate report, the Crown/CEC isn’t even one of the trustees holding title to FK on behalf The Gibraltar Limited Partnership, that also means your assertion “it is the partners that are the legal owners of the property” isn’t even correct in the case of FK either!)

Bearing in mind the GLP also owns two shopping centres in England, neither of its partners can claim to carve “Scottish” (or “English”) assets or interests out of it for themselves. The CE’s only beneficial interest in GLP’s capital assets is a sum of money once it has been dissolved and FK and the other two centres have been sold and any liabilities of the partnership paid off. It’s therefore entirely “convincing” and not in the least “disingenuous” for a lawyer to suggest, if forced to choose, that the “nationality” of that “minority Scottish” sum of money can only be English given it’s an English partnership.

Of course it doesn’t really matter what a lawyer thinks because we’re not construing an Act of Parliament or a legal document here. We’re dealing with the expression (which isn’t a legal term of art) “economic assets in Scotland” in the Smith Agreement. I bet FK never came up during the Smith discussions so now that it has, instead of looking for grievances and conspiracies and accusing (the wrong) public servants of bad faith, why not get some adults in the room to say “We didn’t think about this, how are we going to deal with it considering it does have a bit of a Scottish angle?” On further mature discussion, it may turn out that FK is a loss making liability that Scotland would be well off without. Or that it was bought out of the proceeds of sale out of English property so that Scotland has no “moral” claim on it whatever.

I have read the Law Commission report and refer you to para 2.5. The Crown Estate Commissioners is not a normal legal person. It’s interest in any Scottish asset is by definition and by law an interest held on behalf of the Crown in Scotland. If they have constructed an arrangement whereby that interest cannot be crystalised then they are acting beyond their powers since all land held by the CEC must be held direct of the Crown. Given the separate legal status of the Crown in Scotland, that means the Crown in Scotland. The way to resolve this issue of course is to sell the interest in Fort Kinnaird.

I understand that an English partnership has no separate legal personality distinct from those of its partners as a Scottish one has but that does not alter the situation of partnership property as set out in s.20 the Partnership Act and as explained in the dictum in the Popat case.

Is your point that an investment by the CE in a partnership like Gibraltar is a breach of s.1(3) of the CE Act 1961 (maintaining an estate in land)? If so, I’d agree it’s a bit borderline. It depends on how you define “estate”, I think, but I’d find it hard to believe it wasn’t gone into very thoroughly by Hercules (if not by the CE) on the advice of lawyers who know a lot more about these things than you or I do!

I’m fairly sure FK is not a loss-making liability – it’s now pretty well fully occupied with other potential occupiers banging on the door.

Hector, my friend mentioned to me that if land owners will now have to pay council tax on run down or empty cottages, we will see many of these up for sale very soon which will be a good thing for the community to bring these back into use.

On the issue of whether decentralisation from Edinburgh is a condition precedent hard wired into the Smith Agreement (as opposed to just “thinking out loud” about what might happen after devo) meaning that the legislation must necessarily be more involved than just deleting the relevant CE reservations in the Scotland Act, it’s interesting to note the wording of the Scottish Affairs Committee report:-

“any devolution of the CEC’s responsibilities be conditional on a clear commitment and a detailed agreement, based on the principle of subsidiarity, to the further decentralisation to the maximum extent possible of the CEC’s responsibilities” (para. 88)

Perhaps the less explicit wording in the Smith Agreement was employed consciously to signal a departure from the SAC’s approach. But it’s not about parsing the texts looking for the version one finds most congenial: just ask the Smith delegates: “Did you mean decentralisation to be a condition precedent?”. And if they say “Don’t know”, then the matter just has to be agreed now that it’s been raised by the wording of clause 31.

It’s also interesting to note what the Scottish Affairs Committee (with whom Andy Wightman’s evidence was highly influential to judge from the number of times he’s mentioned) had to say about the CECs being able to continue to invest in Scotland after devolution:-

“we see no principled objection to the CEC continuing its activities in Scotland in the buying and selling of land and property. We recommend therefore that the CEC should be able to buy and sell land and property in Scotland like any other property investor, as part of managing its commercial urban and rural property portfolio on a UK basis.”

More recently we were told that, the beast having been slain, this would allow it to re-emerge, hydra-like, once again to spread the peculiarly vicious brand of fear, misery and criminality that is the CECs’ hallmark. Then we were told it was just too complicated. Perhaps recognising that that doesn’t credit Scots with much intelligence, we’re now told it’s not constitutionally possible. That, if I understand the argument correctly, is because there are two Crowns in the UK, a Scottish one and an English one and never the twain shall meet.

This is a misunderstanding. Between 1603 and 1707, there were three Crowns (England, Scotland and Ireland) in the British Isles all worn by the same person. From 1707 to 1800 there were two (Great Britain and Ireland) but since 1801 there has been only one Crown in the United [clue’s in the name!] Kingdom. Thus, the Union with Ireland Act: “Art 1st – That Great Britain and Ireland shall upon Jan. 1, 1801, be united into one kingdom; and that the titles appertaining to the crown [note – singular], &c. shall be such as his Majesty shall be pleased to appoint. Art 2nd That the succession to the crown [note – singular] shall continue limited and settled as at present.”

Due to the separate history, different laws may apply to the Crown’s Scottish property and it may have different advisors there (Lord Advocate instead of Attorney General etc.) but that’s exactly the same for everybody else with interests in Scotland and rUK: Joe Bloggs owns a farm in England let on a “farm business tenancy” as to which he is advised by a lawyer called a barrister and a farm in Scotland let on a “limited duration tenancy” about which he is advised by an advocate …

But even if I’m wrong about that and there is still a Scottish Crown as well as an English one (and perhaps even a third one keeping its head down in Northern Ireland?), all that’s happening just now is that the management of the Scottish Crown’s assets in Scotland as they exist at present is being transferred from the CECs to the Scottish Ministers and jurisdiction over that which is thus transferred is being devolved. That would not prevent the Scottish Crown, acting through the medium of the CECs (as it does at present) acquiring new assets in Scotland after the transfer date on a reserved basis. So whatever else, it’s not constitutionally impossible.

That last paragraph from “all that’s” makes equal sense if, to reflect reality, you omit the word “Scottish”. But this is another grey area which has emerged from Smith – should the (unitary UK) Crown through the medium of the CECs be allowed to continue to invest in Scotland after the transfer of its existing Scottish assets? Once again, instead of parsing the texts looking for revealed wisdom in the matter, it’s a question of sitting down and reaching agreement on it now. I personally hope the decision is in favour – it’s not in the least bit “muddled” or “incoherent” and to refuse would send just the worst sort of parochial and xenophobic signals. How could any politician credibly advocate a position whereby the government of say, Kazakhstan, can invest in Scottish property but not the government of the UK? It’s a joke!