The Future of Kinloch Castle on Rùm

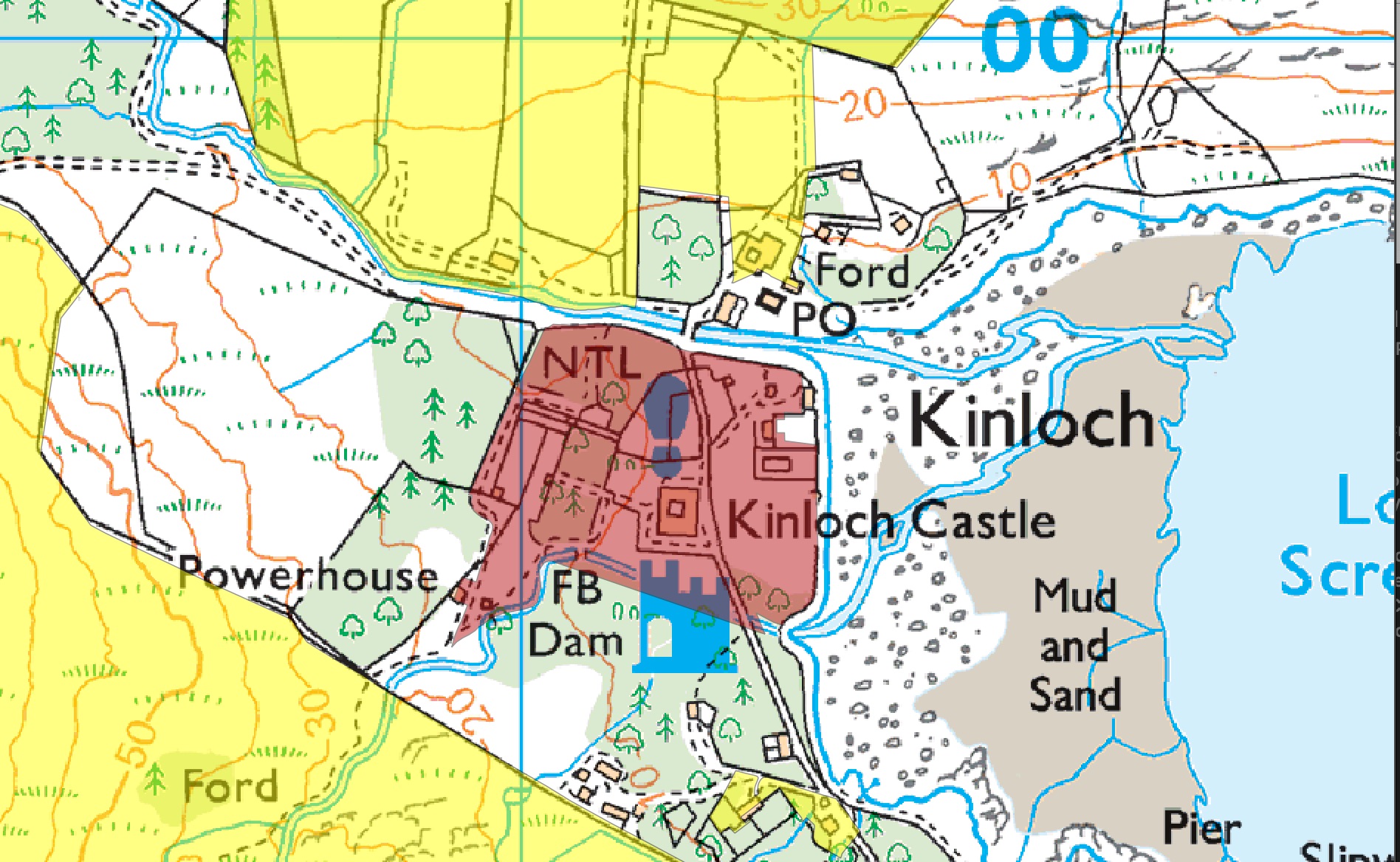

Pictured – Kinloch Castle

I am just back from four days on the Isle of Rùm.

There have been four phases in the history of Rùm.

The first and longest was the pre-clearance period stretching from pre-history up until 1826 when Maclean of Coll cleared 300 women, men and children off their smallholdings and shipped them off to Nova Scotia aboard two ships, the Dove of Harmony and the Highland Lad. Two years later a further fifty were cleared leaving one family of native islanders.

The second phase was when the island was run exclusively as a sheep farm. That ended in 1839. In 1845 Rùm was sold to the 2nd Marquis of Salisbury to begin the third phase – as a hunting estate along with the introduction of Red Deer.

In 1888 the island was sold to the industrialist, John Bullough whose son, George inherited it in 1891. George Bullough was fabulously wealthy and spent his time living a life of leisure. he commissioned the construction of Kinloch Castle, an opulent holiday home which was completed in 1901.

In February 1957, George Bullough’s widow sold Rùm to the Nature Conservancy (now Scottish Natural Heritage) and so began the fourth phase.

One of the conditions of sale (which was included as a burden in the title) was that the island would be used as a National Nature Reserve and it was subsequently designated five weeks later. The designation statement noted that,

“never having been a tourist or mountaineering resort and having no crofters, the island is ideally suited for much field work…”

The stated purpose was the

“safeguarding and perpetuating the natural assemblages of plants and animals which they [the reserves] now contain, plant and animal assemblages which might settle there under more favourable conditions, and special features of geological interest.”

There is no mention of people. In September 1957, a request by the farming tenant to renew his lease was refused. Rum was now no longer a producer of food for the first time in millennia.

Official restrictions were placed on public access which led to furious complaints. The Nature Conservancy’s motives were clear in a letter written by the Chair, Max Nicholson to the Bullough’s lawyers in March 1957 which concluded

“Perhaps we should consider other ways too of making Rum a model Hebridean Community (without Hebrideans)”

So began the fourth phase in Rùm’s history – an island whose only residents would be those employed by the Nature Conservancy.

No crofters, no Hebrideans, no tourists and no mountaineers.

The massive flaw in the whole scheme was the fact that the island was sold lock, stock and barrel (with the sole exception of the Bullough family mausoleum on the west side of the island at Harris).

The castle came with the sale and the Nature Conservancy had undertaken to maintain it “as far as might be practicable” but numerous attempts to secure a sustainable use came and went. It was used for hospitality and accommodation but the fabric deteriorated to the point where it is arguable if it has any future at all.

The fifth phase is in the process of gestation. In 2009, ownership of most of the land in and around the village of Kinloch was transferred to the Isle of Rum Community Trust. For the first time in the island’s modern history, the people who lived on Rùm could look forward to a far greater say in how it was managed.

Today, however, there are doubts as to whether the island’s largest landowner, Scottish Natural Heritage shares the vision they played such a key part in back in 2009. At the heart of the matter is the future of Kinloch Castle. What to do with this bizarre edifice has dogged SNH and its predecessor for over half a century

In June this year, SNH entered an agreement to sell the castle and land surrounding it to a financial speculator, Jeremy Hoskins, a businessman from the north of England and political donor to the Brexit campaign and the Reclaim Party.

The Heads of Terms signed in June 2022 make clear that the proposal is to buy the castle and a large area of land around it (the red shaded area in the map above). The agreement stipulates that Hoskins will own the road or esplanade in front of the castle currently used as the main road to Kinloch and that there shall be no servitude over it. Unfortunately for Mr Hoskins, there is a servitude over it in favour of the Isle of Rùm Community Trust and SNH is in no position to acquiesce to Hoskins demands.

The future of the castle is vital for the island community of 40 or so people only 10% of whom now work for SNH. Children from the island are nowt attending high school for the first time and plans have been developed by Isle of Rum Community Trust for development of the community and facilities.

Despite the Scottish Government’s own commitments under the Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement, the Community Trust has had no formal involvement in the decisions being taken by SNH. No deal should be struck without the active involvement of the Trust and legally binding agreements about the future of the castle.

The current proposals from Hoskins include the transfer of ownership to a charitable organisation but there is no detail on what its objects or governance will be. There are no agreements of any kind with the local community and no clarity on any business plan, future use or how it fits with the longer term strategy for the island, its residents, the NNR and the wider economy.

SNH understandably want to offload this liability but they don’t have to live with the consequences. Hoskins is enthusiastic about the acquisition but, again, won’t have to live with the consequences. He can sell up and walk away at any time.

Those whose futures are intimately tied up with the project are the local community. Sadly, there are far too many examples of well intentioned wealthy men (it is always men) buying up land and property and promising the earth. When such promises are not fulfilled, they walk away. On most parts of the mainland, the situation can, in time, be recovered. On an island like Rùm with no grid connection, no public roads and a fragile economy, any failure can be terminal.

It is not for me to venture any solutions to the future of Kinloch Castle and there have been plenty suggested. It is not an easy job. But one thing is clear. That future has to be openly discussed and debated with the full participation of local people. Any agreed course of action must identify all of the risks and opportunities and proposed mitigations. Governance, investment, and management must all be tied down and agreed.

The Isle of Rùm Community Trust issued this briefing note yesterday.

Unfortunately the current approach by SNH is hasty, incomplete, lacking in community buy-in and fraught with risk. It is time for Ministers to make their views clear on how the situation can be resolved whist respecting the Scottish Government’s policies on land reform, rural development, net-zero, islands and the economy.

Proposals to conclude the sale on 31 October 2022 must be abandoned.

See also this blog by Dave Morris at parkswatchscotland

a great article, thank you

Trying to take control of the road seems like a huge red flag. I hope they find another buyer.

‘Unfortunately, there is a servitude over it in favour of the Isle of Rùm Community Trust and SNH is in no position to acquiesce to Hoskins demands.’

Not following this bit Andy. Is it not a good thing for the RCT to have a servitude!

Hoskins wants the road in front of the castle to be sold to him with no rights of access to third parties. But IRCT has a servitude in its title and so Hoskin’s condition cannot be met by the vendor (SNH)

Thanks. Got it now.

I don’t know the detailed specifics of this case but much of Scotland’s land is used primarily to dodge taxes using an assortment of creative devices. Land is so valuable as a tax dodge that it is unaffordable for other purposes. The resulting extortionate cost and extremely limited availability of land perpetuates the Clearances.

Radical land reform is long overdue in Scotland but the SNP has been watering down and stalling this for much too long, despite efforts by members to do the opposite.

I fully support the objectives of the local community in this case but there is a much wider problem that needs to be addressed. It is extremely disappointing that the SNP’s land reform agenda is so tardy and limited in scope. Sadly, the constitution and rules of the party have been amended in recent years in order to prevent members from being able to influence policies (as they tried to do on land reform, currency and the Growth Commission report, amongst other things). The updated constitution and rules mean that party has effectively become an autocracy and there’s nothing the wider membership can do about this.

Kinloch castle should be bulldozed along eith many other monuments to excess

Delighted to have met you on the boat and hope you had a good holiday. As I explained I had some involvement in the Castle in a previous life before retirement and know the problems with the building. Restoration costs will be in the millions and if that is the solution then it is likely that a wealthy individual is the only candidate. As a community project it would become an expensive burden not only in the restoration but in the ongoing maintenance and management. It is in my opinion the wrong construction in the wrong location with such a high rainfall and unlikely ever to prevent the ingress of water. There are other examples of such ‘monuments’ to wealthy Victorian businessmen across the west, with similar problems. On the community side it is very disappointing to hear of the lack of consultation with the community and the Scottish Government should be telling SNH to step back and actively involve the community in the process. Any sale without community support is doomed in such a location.

Kinloch Castle is the epitome of the phenomenon replicated throughout the Highlands and Islands of wealthy individuals establishing a private domain and retreat for themselves, separate from the local community. Do we really want to continue with this in the 21st century? What merit does the building have other than a historic example of the culmination of the wishes of someone with more money than sense? Why is this ‘white elephant’ worthy of restoration?

Given the condition of the building and its location, I can’t imagine Naturescot’s coffers will be significantly increased as a result of any sale.

In my opinion, it is a redundant eyesore. It should be erased with the stone retained for new builds on the island.

personally I think Kinloch Castle should not be sold unless it has caveats in place that are included to the benefit of IRCT and in No way work against the good of the islanders and residents,

rather than selling, the SNH should support The Isle of Rum Community Trust in refurbishing the Castle to its former glory and let it be run to the benefit of the Rum Community Trust, profits of which could then be used among other things, to provide further accommodation for staff & or for more families to live on the Island or holiday B&B’s providing more income for the island, if this is not done and the Castle is sold to another selfish owner who does not try to get on with the islanders, the Island will be doomed to die a death, due to the inability of having things run to the benefit of the islanders or SNH not having caveats ready at time of sale and the buyer thinking he has bought more than he has which will clearly as has happened in other islands cause animosity between islanders & a Castle owner…

The IRCT must be First n Foremost included in any deal to sell the Castle, That much is paramount going forward..

The problem is that SNH do not have the £millions needed to refurbish the castle. If it is to have a future that money needs to come from somewhere.

The IRCT seem to want control of the castle and access to any profits but without the responsibility that goes with it. I do fully understand the shore road issue and cant believe any purchaser would make its use exclusive to the owners of the castle, anyone who insisted on this must know its not acceptable and will never be given therefore why insist on it. Smells of an egotist bidding purely for publicity and a feeling of importance.

The castle is definitely out of the control of ordinary people and as has been said it will be money (or lack of) that decides its future.