ECHR and the Discriminatory Impacts of Late Registration

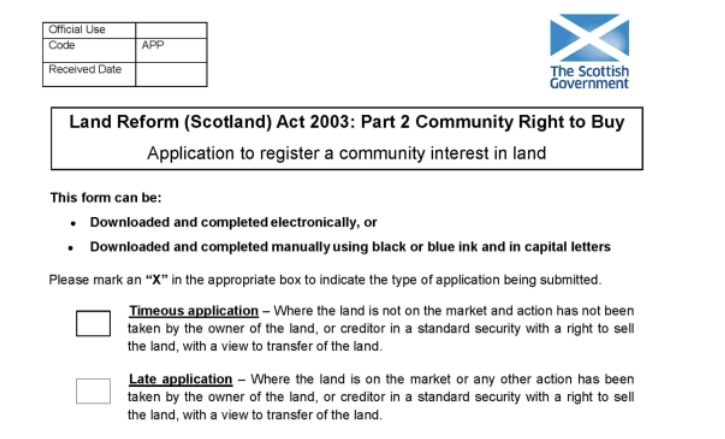

In the section at the end of my previous blog, I highlighted how the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill (the Bill) does not simply extend existing opportunities for community bodies to make late registration applications under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 but creates a new and separate process for determining such applications.

The blog outlined the two routes that would be available if the Bill passes as drafted. To make sense of what follows, it is advisable to digest that information first

I argue that this opens the door for potential legal challenge under Article 1 Protocol 1 (A1P1) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). In this blog I want to set out the argument as to why this may be the case. I am familiar with human rights law in this area but I am neither qualified in it nor an expert.

I may be wrong in thinking that this problem exists but I would rather set it out and have it competently and expertly dismantled, than be proved right in a few years.

ECHR

A1P1 reads as follows

Protocol 1, Article 1: Protection of property

Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international law.

The preceding provisions shall not, however, in any way impair the right of the State to enforce such laws as it deems necessary to control the use of property in accordance with the general interest or to secure payment of taxes or other contributions or penalties.

The late registration provisions have been in existence since the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 came into force in June 2004. To my knowledge they have never been challenged under the provisions of A1P1. The provisions initially applied only to rural land but were extended to cover the whole of Scotland in April 2016.

The Bill, however, change things as it introduces discriminatory elements to the procedure depending on the circumstances of the landowner and the sale of land. I will illustrate these in a moment but these changes could bring into play Article 14 of the ECHR which reads as follows

Article 14: Prohibition of discrimination

The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.

Article 14 is not a standalone provision of the treaty. It only has relevance in relation to any of the rights and freedoms enshrined in the rest of the Convention. In other words if the right to a family life cannot be enjoyed by someone due to direct or indirect discrimination then it will be unlawful under Article 14.

And for Article 14 to be engaged in any case, it is not necessary that any of the substantive human rights protections are violated (for example, A1P1). In the words of the ruling by the Grand Chamber in Carson and Others v. The UK, “the application of Article 14 does not necessarily presuppose the violation of one of the substantive rights guaranteed by the Convention” [1]

A previous Supreme Court case (Salvesen v Riddell) concerning agricultural tenancies, was found to be incompatible with the rights conferred under A1P1 in part because of Article 14 discrimination. [2]

This opens the door for potential legal challenge to Section 2 of the Bill (the amended late registration provisions) not necessarily because it is incompatible with A1P1 per se but because of the discriminatory way in which the rights that are protected under A1P1 may be enjoyed. As the Supreme Court stated in Salvesen v Riddell in relation to Article 14.

All that needs to be said is that the declaration that it contains, which is that the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in the Convention are to be secured without discrimination on any ground, informs the approach that is to be taken to the question whether there is an incompatibility with A1P1. [3]

For an issue to arise there must be a difference in treatment of “persons in an analogous or relevantly similar situation”. [4]

A difference in treatment will be discriminatory if it “‘has no objective and reasonable justification’, that is, if it does not pursue a ‘legitimate aim’ or if there is not a reasonable relationship of proportionality between the means employed and the aim sought to be realised.” [5]

DISCRIMINATION IN THE BILL

The potential discriminatory effect in the Bill is in relation to the different treatment and impact on property rights of landowners who, I argue, are “in an analogous or relevantly similar situation”.

Consider four landowners who are all in the same position of wishing to sell 500 ha of land that they own.

James is a landowner who owns a 500 ha landholding. He decides to sell it and contacts his preferred estate agent. The estate agent advises him that they have a number of potential buyers on their books. Having considered a number of offers from some of these buyers, James decides not to go ahead with the expense of an open market sale and strikes a deal with one of these buyers to sell his landholding.

Mary also owns a 500 ha landholding and she decides to put it on the open market.

Susan owns a 1001 ha landholding and she too decides to sell 500 ha part of her property. Under the provisions of the Bill, she is required to notify Scottish Ministers who, in turn, may invite a community body to make a 39ZA late application.

Gordon also owns a 1001 ha landholding but it is split into two parts by a railway line with 500 ha to the north and 501 ha to the south. He decides to sell the northern part. Despite owning a landholding just the same size as Susan’s, his landholding does not qualify as a large (>1000 ha) landholding because it is not contiguous and thus he is not required to notify Scottish Ministers. he puts it on the open market.

There is no community right to buy registered against any of their land.

James, Mary, Susan & Gordon are all wishing to sell a 500 ha parcel land but they face very different prospects in doing so.

James is in the best position. He gets a quick sale and doesn’t have to involve Scottish Ministers or any community body, neither of whom have any knowledge of the sale having taken place.

Mary and Gordon both face the risk of a late registration from a community body which, if made, will be tested against the more stringent tests introduced by the 2015 Act. If such an application is made, they face a delay in selling and, if a late registration is granted, face a further delay and will have to sell at a price set by the District Valuer.

Susan is in the worst position. She has to notify Scottish Ministers about her proposed sale. Any community body can use the existing (more stringent) late registration procedures under the 2003 Act as amended or might be invited to apply for a late registration by Ministers and be assessed against the less stringent tests introduced by the Bill.

The potential discrimination is potentially two fold.

The first is the discriminatory impact as between James on the one hand free to do as he pleases with his 500 ha and Mary, Susan and Gordon on the other, who, in different ways, are all seeking to sell the same amount of land.

The second is the discriminatory impact as between Susan on the one hand and Mary and Gordon on the other. All three are subject to a potential late registration and community right to buy but Mary and Gordon are in a far better position, They are not required to notify anyone, can move fast and, if any application is made, it will be assessed against stringent criteria.

Susan, on the other hand has to inform Scottish Ministers, is not in control of the timetable, and faces the prospect of a late registration to be judged again far lax criteria than Mary.

In other words, 3 landowners wanting to sell 500 ha are treated differently in relation to both the prospect of a late registration and in relation to how the mechanism is applied.

Furthermore, this discrimination arguably ‘has no objective and reasonable justification’ and nor is there “a reasonable relationship of proportionality between the means employed and the aim sought to be realised.”

CONCLUSION

I may well be wrong in all of this.

But given that Article 14 was never in play before now, late registration provisions could be assessed against A1P1 alone. Now that different landowners face different prospects despite being “in an analogous or relevantly similar situation” and with little justification for the new less stringent test or the 1000 ha threshold, Article 14 may well have to be considered.

Discuss.

NOTES

[1] Carson and Others v. the United Kingdom [GC], 2010, at [63] https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.asp?i=001-97704

[2] Salvesen v Riddell https://supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2012-0111

[3] Salvesen v Riddell at [45]

[4] See para 32 in Guide on Article 14 of the ECHR Prohibition of Discrimination https://ks.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr-ks/guide_art_14_art_1_protocol_12_eng

[5] See para 59 in Guide on Article 14 of the ECHR Prohibition of Discrimination https://ks.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr-ks/guide_art_14_art_1_protocol_12_eng

One minor point. Susan is assessed against the same criteria as Mary and Gordon is a late application is lodged. The Bill provides a route to the existing late application procedures and does not replace them.

Not the way I read the legislation – the late application provisions of the original 2003 Act (as amended) do not apply to late applications under the Bill which are specifically excluded – see Section 2(2) “is not an application to which section 39ZA applies”

The explanation you give looks likely to be correct from what i know. This perhaps takes us back to the original ScLandComm research in 2018, stating that the real issue with potential for causing problems is ‘concentrated ownership’, not scale. Given what you say is correct, it appears to have been a mistaken policy choice to nevertheless go for ‘scale’ as a marker for state intervention , perhaps because it’s easy to identify, even if somewhat arbitrary and not necessarily related to the problem of land availability. The suggestion of giving “some body” the right to declare ‘action areas’ where concentration of ownership seems to be a problem should be revisited. It would not be too different to ‘housing action’ or ‘slum clearance’ initiatives in the past. “Under the 1974 Housing Act, Local authorities were empowered to declare HAAs with the intention of …removing the underlying causes of housing stress” [as per a search for HAAs]

Thanks, Mike.

If the Bill is passed as it is in relation to late applications, the 2003 Act as amended will then have provisions for CRTB and the existing provisions for late registration BUT it will then exempt or carve out from those, the new 39ZA test for >1000ha holdings

At this point there needs to be an objective and reasonable justification and proportionality etc in line with Art14

This is where I struggle…….

The 1000ha threshold was only ever described by SLC as a proxy for situations where concentrated power impacts on local communities. SG has given no persuasive justification (arbitrary is how many have described it). When Ministers talk about extending it downwards they don’t appeal to any objective justification for 1000ha but merely to the additional costs of bringing it down further. And the Minister herself admitted that most community acquisitions are for smaller areas of land.

The 1000ha, the prior notification AND the relaxed criteria ALL need to be justified in terms of the reelvant Art14 tests. Maybe they can be. I’ve just not seen anything that even attempts to address this point.