Scottish forestry still in hands of an elite.

The following was first published as a Guest Column in the West Highland Free Press on 10 August 2012.

The subject matter is one of a large number of vital topics that should be addressed by the Scottish Government’s Land Reform Review Group.

I have no idea where the paper upon which these words are printed came from but there’s a fair chance that you are holding in your hands the produce of a small farm in Scandinavia. Perhaps it came from a company called Södra, the third largest producer of wood pulp in the world and a co-op owned by 51,000 forest owners in southern Sweden. Or perhaps it was produced by Metsä Group from Finland, one of the largest forest products companies in the world operating in over 20 countries and wholly owned by the 125,000 Finnish forest owners who form the Metsäliitto Cooperative and who on average each own a 40ha landholding.

The fact that trees grow just as well in Scotland should, all things being equal, mean that here also there should also be a large timber processing and pulp industry owned by tens of thousands of farmers and crofters. Dream on.

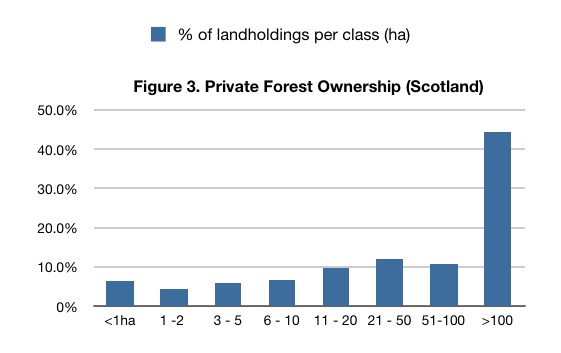

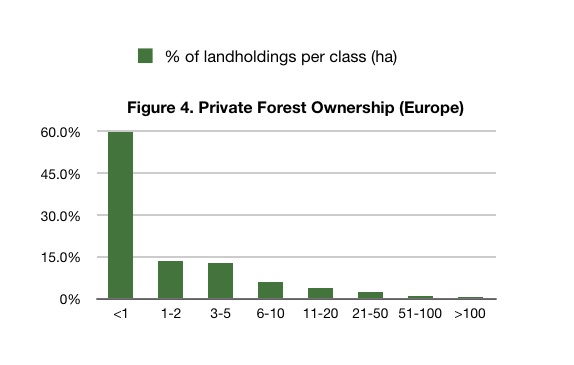

Earlier this year I inquired into the landownership pattern of Scotland’s private forests and found that the Forestry Commission collects no data on the topic and as recently as 2011 was providing statistical data to the United Nations based upon a UK wide sample from 1977. What I found astonished me (see graphs below). Over 44% of private forests in Scotland are over 100ha in size and account for over 94% of the forest area. Across Europe most forests are small-scale and less that 1% are over 100ha in size. Over half of Scotland’s private forests are owned by absentee owners and a third don’t even live in Scotland.

Land use in Scotland is distinctly odd. Not only do many more people own land in France, Switzerland and Italy but children have legal rights to inherit it. Farmers are also foresters. There are no big estates with tenants. Public forests too are owned by local communities. In France, for example, there are 11,000 forest communes – 30% of all communes in the country – and they own around 3 million hectares of forest or around 20% of the total forest area of France.

A friend of mine recently returned from a visit to Romania where post communist land reform has returned land to families and to communities. In the Apuseni mountains, she learnt how every individual is entitled from birth to 5 cubic metres of wood from the commune forests per year. Every young couple getting married is given 20-30 cubic metres to build a house. It’s hard to envisage this in the Pentlands, in Sutherland or in the Cairngorms.

What the European experience demonstrates is that small scale landownership can deliver large scale economic success through co-operation. It is possible to envisage a Scotland of small-scale forestry, of farm forestry, of small-scale rural businesses and of community forests. This is the reality in France and Finland but it is a million miles from the nihilistic corporatist model we have developed in Scotland where celebrities and wealthy individuals from the UK and abroad are given free rein to exploit the public funds provided to expand Scotland’s forests as a source of personal tax free aggrandisement.

The reasons why Scottish private forestry is dominated by large-scale absentee landowners is of course partly down to the past. Historically in Scotland only a tiny elite owned land and all farmers were tenants. Until 2004, the law stated clearly that trees belonged to the landlord and so farmers have never been forest owners. Children have never had legal rights to inherit land in Scotland and thus landholdings continue to be passed to (typically) the eldest son. Indeed it was land reforms one hundred years ago that created the impetus for large co-operatives like Metsäliitto.

Quite apart from Scotland’s legal history, it has been the political choice of a succession of UK and Scottish Governments to support wealthy elite interests in developing Scotland’s forestry industry with grants and tax breaks being the main incentives to plant new forests. Whilst I was a forestry student at Aberdeen University, folk like Terry Wogan and Shirley Porter were buying land in Caithness and planting it with conifers. It was this stupidity that, among other events, prompted my interest in matters to do with landownership and use.

The Scottish Government has a green vision of expanding forest cover to mitigate climate change and has set ambitious goals. Forest cover is set to increase by 650,000ha which will increase forest cover in Scotland from from 17% of the land to 25% by 2050. Funding of £36 million per year has been earmarked over the next 4 years – around £500 million by 2025. That’s a lot of money. But who’s benefiting from this largesse?

In June, Stewart Stevenson MSP, the Minister for Environment and Climate Change announced a new £6 million Scottish Land Fund to assist communities buy land over the next 3 years. Imagine if 20% of the Scottish Government’s forestry grants over the next 10-20 years were to be allocated to communities – that would represent an investment in rural communities of a stunning £100 million. This is money that is committed to tree planting and which is entirely in the gift of the Scottish Government. Others (farmers, landowners, industrial interests etc.) could also be allocated a share. Trees don’t really much care who owns them and and so just as many trees could be planted but instead of absentee investors and corporations seeing all the benefits, community landownership could be extended on an epic scale.

Alternatively of course, we could proceed with business as usual, with elite financial and corporate interests snapping up the land and monopolising the public funds to further their own financial interests. It is up to us what direction we take. We, through our elected representatives and the powers of the Scottish Parliament, have full control over most of what matters. Let’s hope that the recently appointed Land Reform Review Group grasp the opportunity to conduct an in-depth analysis of the possibilities.

UPDATE 1941hrs 12 August. Sue Guy reminds me that she and Andy Inglis wrote a paper entitled “Rural Development Forestry in Scotland: the struggle to bring international principles and best practices to the last bastion of British colonial forestry. Nothing much has changed.

Did I read that right? You think landowners and industrial interests “etc” should elegable for a share of the money????

I have no fixed view on that at the moment.