Land Reform (Scotland) Bill (1)

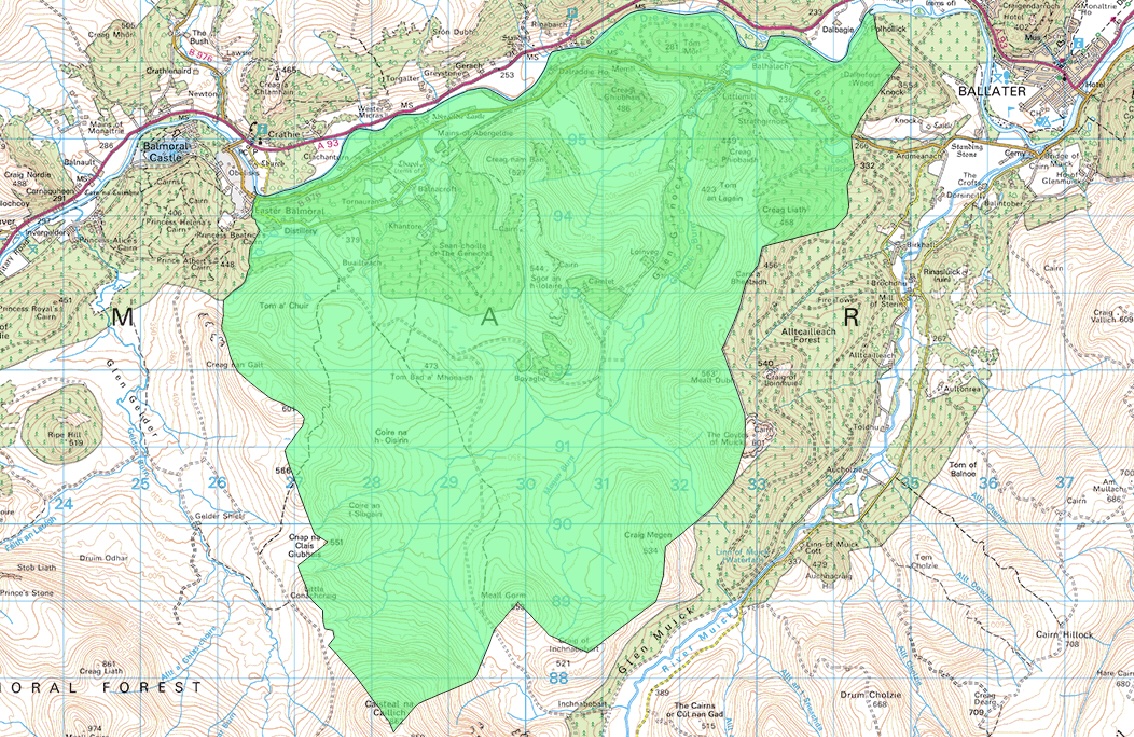

(Pictured above the 4703ha Abergeldie Estate sold for an undisclosed sum in 2022)

The Land Reform (Scotland) Bill was introduced to the Scottish Parliament on 13 March 2024 (see end of blog for all the documents). This blog is designed to summarise the key provisions, reflect on the process of developing them, comment on them and assess their likely impact. There is a lot more to write about these matters but I want to keep this first blog reasonably compact.

SUMMARY

- 75% of this bill relates to reform of agricultural tenancies and the remaining 25% relates to what Scottish Ministers call land reform.

- The Bill is an amending bill. It amends the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 and the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 by inserting and modifying sections of these Acts. It is thus not easy to understand the provisions without some knowledge of those two Acts.

- The Bill leaves a lot of important detail to worked out later in secondary legislation. This is not an ideal approach.

- The Bill does not include important recommendations from the Scottish Land Commission nor does it implement many of the proposals raised in the consultation. There is no Public Interest test, no strengthening of the Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement, and restrictions on land ownership to EU and UK registered entities for example.

- Given the scope of coverage of the proposals, the nature of the land market in Scotland, the complexities of the Right to Buy and the absence of a Public Interest test, the Bill is unlikely to have any meaningful impact on the pattern of landownership in Scotland.

STRUCTURE OF THE BILL

The Bill is in three Parts.

Part 1 deals with the management and transfer of large landholdings (pages 1-28)

Part 2 deals with reform of tenancy law in relation to land and includes (page 28)

Part 3 covers technical legislative matters (pages 65 – 66)

Schedules relate exclusively to Part 2 (67 – 110)

This blog deals only with Part 1 which comprises Sections 1-6 on pages 1 – 28 of the Bill.

Section 1 Community-engagement obligations in relation to large land holding

Section 2 Community right to buy: registration of interest in large land holding

Section 3 Modifications in connection with section 2

Section 4 Lotting of large land holding

Section 5 Modifications in connection with section 4

Section 6 Establishment of the Land and Communities Commissioner

There are four substantive sections to consider – Section 1, 2, 4 and 6.

SUBSTANTIVE POLICY

The two substantive policies that Part 1 of the Bill is designed to achieve are

- to increase the accountability of those who own large landholdings

- to introduce new powers of intervention through pre-notification of proposed land sales and an enhanced community right to buy and a transfer test when large landholdings are offered for sale.

Accountability

Accountability is to be achieved by community engagement obligations for owners of large landholdings (over 3000 ha) and a duty to prepare land management plans setting out how owner is complying with (among other matters), the outdoor access code, the code of practice on deer management and how land is managed to contribute toward net zero. Secondary legislation may require owners to give consideration to a reasonable request fort a community body to lease land.

These duties are to be enforced by a new Land and Communities Commissioner to be added to the existing membership of the Scottish Land Commission. Alleged breaches can be reported to this new person but only a very limited number of people can report – 3 public bodies, the local authority or a community body established under the 2003 Act. Most places do not have such a body. Community councils and individuals cannot report any alleged breaches. The Commissioner can investigate breaches and impose a fine of no more than £1,000 for a failure to provide information and £5,000 for failure to comply with the duties placed on large landowners.

Intervention in Land Sales

The new powers of intervention apply to landholdings above 1000 ha. The landowner who intends to sell part or all of any such holding must notify Scottish Ministers of their intention to sell. Ministers may not intervene where the proposed transfer is exempted by the existing 2003 CRTB legislation. These exempt transfers include a transfer between spouses, a gift of land, a transfer between companies in the same group and a few others.

Two consequences can arise from any intervention.

The FIRST is that, if there is a community body already established then they have the opportunity to make an application for a late Community Right to Buy (CRTB) registration under the existing provisions of Part 2 of the 2003 Act. Ministers may only intervene and put a hold on any sale for 40 days and only where they consider that it is likely that an application for the right to buy will be made and where there is a reasonable prospect of that application being registered.

The SECOND is that Ministers have a power to order the mandatory “lotting” of any land being sold so long as exceeds 1000 ha or at least 50ha where a number of parcels totalling over 1000 ha are being offered for sale. Ministers may make a lotting order that land to be sold in specified lots and can have regard to have regard to how often land comes on the market locally and the concentration locally.

There is no control over who buys these lots beyond requiring that no one person (or connected persons) should acquire more than one of the specified lots. If the lotting decision makes land less commercially attractive, Ministers must review the decision if owner asks for it after one year and must compensate owners for loss or expense incurred in complying with procedural requirements or arising as a result of the impact of the lotting decision

Importantly, Ministers may make a lotting decision that land can only be transferred in lots if they are satisfied that ownership of the land being transferred in accordance with the decision would be more likely to lead to its being used (in whole or in part) in ways that might make a community more sustainable than would be the case if all of the land were transferred to the same person.

And that, in essence is all there is to it in relation to reforming how land in Scotland is owned.

Thats it.

DEFINITION OF LARGE LANDHOLDINGS

A large landholding is defined as a single or composite holding of over the specified threshold. This is 3000 ha for community engagement and management plans (or over 1000 ha and more than 25% of an inhabited island) and 1000 ha for intervention in sales (no island variation).

A single holding is the whole of a contiguous area of land in the ownership of one person or set of persons (including where land is owned jointly). It follows that a dispersed landholding across Scotland of sub – 1000 ha holdings is not a large landholding neither is one that, being bisected for example by a railway, results in sub -1000 ha parcels that are not contiguous.

A composite holding is where there are two or more parcels of land that are at least partly contiguous owned by the same beneficial owner. Company A may own 600 ha and the holding has a border with another parcel of land of 500 ha in extent owned by Company B. if companies A and B are both owned by the same company or person, it is defined as a composite holding.

As another example, if 500 ha is owned by Jean Smith, 500 ha by the Trustees of Jean Smith and 500 ha by Jean Smith Ltd. then this is a composite holding if Jean Smith in effect owns all of the 1500 ha so long as they holdings are partly or wholly contiguous with each other. If they are separate and only 100m from each other, none of the holdings are within scope of the legislation.

If an owner owns 50,000 ha across Scotland in 200 separate holdings but only 5 of them exceed 1000 ha, then only those 5 are caught by the intervention powers and none are covered by the community engagement and land management plan duties (which are for holdings over 3000 ha).

COMMENTARY

Background

It is worth reminding ourselves of how we got to this point. Back in March 2019, the Scottish Land Commission (SLC) – the Scottish Government’s statutory advisers on land reform – provided a report to Ministers entitled Review of Scale and Concentration of Land Ownership. It recommended the following three substantive policy changes.

- a public interest test for significant land transfers to be exercised by local authorities to consider, among other matters, whether any transfer should take place as proposed (in effect tor regulate who buys the land)

- community engagement and management plans for landholdings above a defined threshold and,

- putting the existing (voluntary) land rights and responsibilities statement on a statutory footing and introducing statutory reviews of the the extent to which the principles within it are being followed by landowners.

In a follow up report on legislative proposals published in 2021, the SLC expanded on these recommendations. It noted, for example, that to be effective, the proposals should cover conventional sales of land together with inheritance, sale of shares in companies owning land and changes in trusteeship of trusts.

It also noted, as part of a review of existing legislation that there was an important gap

“within the existing legislative framework is that it offers no support to proactive individuals, families, and businesses within the local community, who may wish to acquire access to land for their own purposes”.

The SLC also observed that.

“The measures will not, on their own, deliver the longer term systemic change in patterns of

land ownership that are required to realise the full benefits of Scotland’s land resource. Achieving this will require more fundamental policy reform, probably including changes to the taxation system. The need for such reform was also identified in the recommendations made by the Land Commission in 2019 and is the subject of ongoing policy work.”

The SNP manifesto for the 2021 election contained the following commitment.

Backing Community Ownership

We will bring forward a new Land Reform Bill. It will ensure that the public interest is considered on any particularly large scale land ownership and introduce a pre-emption in favour of community buy-out where title to land is transferred.

The Scottish Government’s Programme for Government for 2021 – 22 committed to taking forward a new Land Reform Bill that would.

“address the concentration of landownership in Scotland, including a public interest test“

In August 2021 the Scottish Government, in its Programme for Government stated that it would introduce a Land reform Bill and that,

“The Bill will improve transparency of land ownership, further empower communities, and help ensure that large-scale landholdings are delivering in the public interest. It will also modernise tenant farming and small landholding legislation“

The consultation carried out by Ministers in 2022 consulted on a range of proposals.

The Ministerial Foreword claimed that,

“We are driving forward reform to historically iniquitous patterns of land ownership, but doing so with an eye to contemporary challenges and future opportunities“

The paper proposed the three SLC recommended changes plus additional measures including,

- new conditions on those in receipt of public funding for land based activities

- a new land use tenancy

- restrictions on landownership to legal entities registered within the EU or UK

- a broad proposal for tax reform

What has Changed?

Two of the key SLC recommendations have been dropped. There is no public interest test and no statutory underpinning for the land rights and responsibilities statement. The only one that survives is the community engagement and land management plan proposals.

All of the additional proposals in the Net Zero consultation paper have also been dropped.

The Public Interest test is now a Transfer test.

The consultation paper stated that,

“The SLC proposed to apply the public interest test to the prospective buyer of the land, on the basis that the purchase could exacerbate scale and concentration of landownership if the buyer already held land in the area. We consider that in many situations applying the test to the seller may be more beneficial in meeting our land reform aims. We therefore propose a dual approach.

In order to avoid creating new issues of concentration, a test would also need to be applied to the buyer, who may already have other land holdings“

This test has been dropped. Any person who already owns substantial areas of land is free to acquire what is being offered for sale whether as a whole (where no lotting decision made) or any lot where a lotting decision has been made.

Whereas before it was designed to regulate who bought land above the defined threshold, now it is merely a power (to be used or not) and to be exercised by Ministers rather than by local authorities as proposed by the SLC. The Transfer Test facilitates possible late application to register land under CRTB and a possible mandatory lotting (but with no control over who buys other than no one entity can buy more than one lot).

The measures fall far short of what most of us following developments believed would be in the Bill. Even those measures were fairly modest – which is why the SLC said in 2019 that the measures will not, on their own, deliver the longer term systemic change in patterns of land ownership that are required to realise the full benefits of Scotland’s land resource.

But that even those modest measures have not found their way into the Bill. Instead they have been replaced by another legalistic and bureaucratic processes for volunteers in communities to try and navigate. Indeed so bureaucratic and interventionist is all of this that there are certain to be legal challenges

This is all a potential nightmare of bureaucracy.

IMPACT

What impact are these measures likely to have on Scotland’s concentrated pattern of private landownership – a pattern which I revealed a few days ago to be getting even more concentrated.

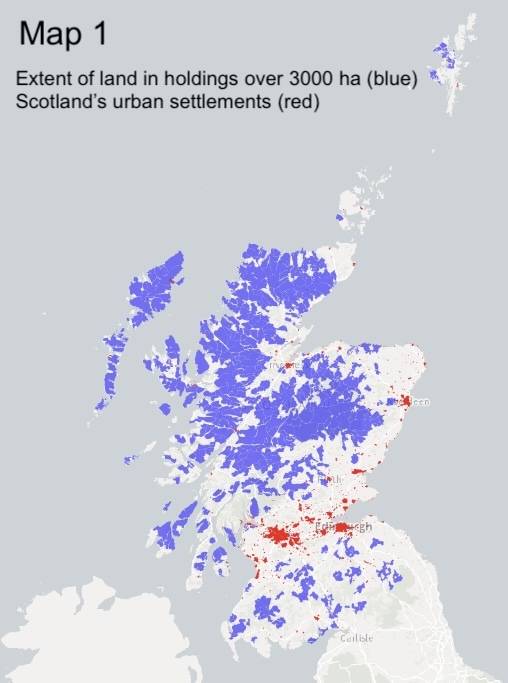

Map 1 below shows the extent of land in Scotland covered by landholdings of over 3000 ha in size. These are the holdings covered by the community engagement and management plan requirements. Such land covers 3,271,210 hectares of land (42.5% of rural Scotland or 41.5% of Scotland in 405 separate landholdings. An initial analysis of those holdings that make ups composite holdings has been undertaken which merges 24 holdings into 8.

The land coloured blue in Map 1 is the land held in holdings of over 3000 ha. Because of the contiguous rule, some of this will not in fact be over 3000 ha as they will be bisected by a railway or trunk road but I have not had time to analyse such holdings. The map also does not reveal where there might be inhabited islands with qualifying holdings of over 1000 ha. I will try and do this in the next few weeks.

The red areas are Scotland’s urban settlements of over 500 population. Without doing any sophisticated analysis, it is clear that most Scottish communities will not be involved in any engagement over land the management of large landholdings.

Map 2 below shows in green the extent of land held in landholdings over 1000 ha. Again, I have not excluded those where there is a modest break in contiguity due to a railway etc. Such land covers 4,368,880 hectares of land (57.6% of rural Scotland or 55.5% of Scotland) in 1068 separate landholdings. A very quick analysis suggests that allowing for composite landholdings this number reduces from 1068 to 988 but further work is required to confirm this.

Community Engagement and Management Plans

The starting point for any analysis of impact is the land that is within scope of the Bill. For community engagement and management plans, this covers just over 40% of Scotland held in the largest landholdings of over 3000 ha. The provisions for management plans are probably the only meaningful part of the proposals analysed in this blog. For the first time there will be some accountability for owners intentions and plans. In time these could become the basis for greater conditionality in public funding and stricter compliance regimes around, for example deer density and woodland regeneration.

Transfer Test

The starting point for analysis the impact of the transfer test is that it brings within scope land covering 55% of Scotland. There is no impact on the remaining 45%.

But the transfer test only applies where land is being offered for sale. It excludes inheritance, land transferred via the sale of shares in the landowning company, statutory transfers under crofter or agricultural tenant right to buy etc. Much of Scotland has never been for sale in recent years. Around 30-40% has stayed in the same hands for over 50 years and around 15-20% for over a century, some dating back to the 12th century.

So how much of the land in scope of the Bill is offered for sale each year? In a recent report I analysed major rural land sales in 2020, 2021 and 2022. The Table below highlights the number of sales of over 1000 ha for each of the years. I will publish a separate blog on the detail of these sales but the average number of sales over the three years was just over 8 properties covering just over 25,000 ha each year. This equates to 0.3% of Scotland’s rural land being offered for sale each year.

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | TOTAL no. | Total ha. |

| 13 | 5 | 7 | 25 | 75,055 |

Of those 8 sales, it is doubtful if any would have had an eligible CRTB body associated with it and so the right to buy could not be applied for. Some land will be under agricultural or crofting tenancies and the tenant will have a right to buy. If we presume that lotting may be made mandatory in one or two at most, then that covers 2 properties covering an average of 6,000 ha. Given the way that lotting has to be designed, those lots will then be sold to third parties, some of whom may own land elsewhere thus increasing the concentration of private landownership in Scotland.

The likely impact on the wellbeing of any community or on the pattern of landownership is likely therefore to be almost non-existent. Indeed, even if all of the land was sold to people who did not already own land in Scotland, an additional 8 landowners would mean that by 2100, 50% of Scotland would be owned by 1041 landowners as opposed to 433 today.

OBSERVATIONS

I will finish this blog by highlighting a number of issues that I have identified with the Bill’s provisions.

Role of Scottish Ministers

The Bill yet again centralises power in Edinburgh by giving Ministers a wide range of powers to make decisions about land in Dumfries-shire, Aberdeen-shire and Argyll. These decisions are best made by the democratically elected local government in those areas.

The Bill also gives powers to Ministers to decide whether they should lot land that they themselves wish to buy. In 2022, Scottish Ministers acquired the Glen Prosen Estate in Angus to be managed by Forestry and Land Scotland. It is not accepted practice to have a regulator of the land market also being a player in it. Of there 988 holdings of over 1000 ha, Scottish Ministers or organisations accountable to them own 168 landholdings covering 489,934 ha or around 12% of all the land within the scope of the transfer test.

Lotting

Scottish Ministers will decide lotting application on land they own. They decide whether their own land should be lotted and and can ask themselves to review a decision made by themselves about a lotting decision on land owned by themselves

Lotting is common commercial practice when owners sell land. Many estates are sold in lots to maximise the aggregate sale price. A typical small estate 2000 ha estate might have 10 houses, 2 or 3 tenants farms tenant farms some woodland and some housing plots. A large upland hunting estate and shooting lodge will normally be does as one package.

Those that are not lotted are usually not lotted precisely because to do so would risk lowering the price achieved. By imposing lotting, not only will Minister be likely to expose themselves to compensation claims, there will be no control over who buys these lots. This seems a waste of public money.

Land and Communities Commissioner

The proposed Land and Communities Commissioner has the role of advising Ministers (as part of the statutory functions of the Scottish Land Commission) but also acting as a regulator by receiving and adjudicating on complaints. it is not clear that these roles are compatible when, for example, some of these complaints may about land owned b y Scottish Ministers or about land where the Commissioner is providing advice about looting for example.

Crofting

No account is taken of crofting tenure and its interactions with the land management, community engagement, CRTB and lotting powers. This is a major omission that I would expect the Scotland’s crofters to have something to say about.

Avoidance

Let us assume that a lotting decision is made to split a 2400 ha property into three parcels of 800ha each. no one person can buy more than one lot. But there’s nothing to prevent them acquiring the other lots later. Imagine I wish to buy the 2400 ha. I can get my friends Susan and Jim to buy the other two lots and then when the dust is settled they sell them to me.

CONCLUSIONS

Land reform attracts a disproportionate share of wild and rhetorical claims by politicians about the impact of various land reform measures. Back in 1999, for example, it was claimed that the the community night to buy “would effect rapid change in the pattern of land ownership”. Twenty years later, there have been 266 applications to register land under the CRTB provisions of which 223 have been deleted or refused, 24 have been activated and 19 are registered. The total extent of land acquired is 18,700 ha or 0.25% of real Scotland – 0.0125% of rural Scotland each year.

Rapid change indeed.

The Cabinet Secretary, Mairi Gougeon, who introduced this Bill claimed that,

“We do not think it is right that ownership and control of much of Scotland’s land is still in the hands of relatively few people. We want Scotland to have a strong and dynamic relationship between its land and people.

We want to be a nation where rights and responsibilities in relation to land and its natural capital are fully recognised and fulfilled. That was our aim in 2016, and it remains our aim today.

This bill sets out ambitious proposals to allow the benefits and opportunities of Scotland’s land to be more widely shared.“

She is correct that it is not right that ownership and control of Scotland’s land is still in the hands of relatively few people. But she is wrong to imagine that these proposals are going to do anything about it anytime soon.

This Bill is the least ambitious land reform bill ever introduced to the Scottish Parliament. It contains excessively bureaucratic, legalistic mechanisms to intervene in a vanishingly small number of instances with no prospect that much will change as a result.

Bills can only be amended within “scope”. In other words, if and when when Parliament has approved the Bill at Stage 1, there is no scope to revise the fundamentals, or add new policy proposals. One can only amend the provisions that exist (by altering thresholds, changing management plan requirements etc.) Thus, if Parliament passes this Bill at Stage 1, those who want to see radical land reform are going to have to think carefully about how much effort it is worth expending on trying to improve the Bill.

With the abandonment of the Public Interest test, nothing on tax, no controls on offshore entities, no conditions on public money no regulation of who can buy the land being sold, it is hard to see how the claims made for this Bill can be sustained.

KEY DOCUMENTS

Land reform in a Net Zero Nation (2022 consultation paper)

Bill and accompanying documents introduced to Parliament

Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment

Child rights and wellbeing impact assessment screening document

Islands community impact assessment (ICIA)

Scottish Land Commission summary key research and evidence informing the Bill

No great surprise there then. The timidity only gets greater as time passes. It’s not as if the landed are about to vote for them. Why are they so reluctant to do anything meaningful.

Cos the landed own them

No surprises there from scotgov.

Its a bit like the guy who fixes the car radio and the mirrors, but doesnt have the balls to fix the blown engine..

Another great analysis Andy. The current government isn’t listening. Maybe a Scottish Labour government will!

What can we do to stop this Bill progressing in its current form?

You cannot do anything to stop it progressing. Only MSPs can do that by voting it down at Stage 1. Before that the Committee will take evidence and produce a report. If you want to influence the Bill then respong to the Committee’s call for evidence is worthwhile.

Hi Andy,

Great analysis as ever.

The bill is a “paper tiger”.

Is there one aspect that we should all concentrate on?

For me, having co-led on a Place Plan for Ardgour, with great push back from the estate on radical housing policies, it would be the public interest test when an estate is sold or if the ownership through a Trust has a change of membership-or even better a five year review?

Your thoughts?

Thanks Michael

I think the management plan and community engagement are the most useful but need further work. I think a lot of these issues could be sorted by Councils being more pro-active with compulsory purchase. I know it can be expensive but there is law reform on the way.

Surely an awful lot of the land in the map above is owned not by private individuals but by charities? I’d be interested to see his much of it’s privately owned. I don’t think the third sector owned land will be affected by this Bill as it’s never coming up for sale. But this style of ownership can be an issue if you’re looking for land for affordable housing for example. I disagree with your suggestion that the local council should decide about lotting – I don’t think they have the capacity to take on these big landowners. It would actually take a lot of political clout to force them to do this. All the landowner needs is a hotshot lawyer and they can easily get the local coonsil to back off – they just won’t want to take the risk.