Land Reform – 25 Years of performance politics

With Stage 2 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill proceedings now concluded, it is time to take stock of where we are, not just with the Bill, but with the wider land reform agenda. In this blog I want to discuss four important aspects of this question.

ONE: Where Stands the Bill?

In relation to Part 1 of the Bill, nothing has changed to alter my original view that this Bill will achieve next to nothing in tacking the structural features of Scotland’s landownership system. It does not deliver on the recommendations of the Scottish Land Commission, nor what was consulted upon in advance of the Bill, and will not achieve the aims set out in the Bill’s Policy Memorandum.

It will have little impact, beyond creating new complexities, friction and conflict in the land market for no evident gain. As I argued in March 2024, this Bill remains the least ambitious land reform bill ever introduced to the Scottish Parliament. It contains excessively bureaucratic, legalistic mechanisms to intervene in a vanishingly small number of instances with no prospect that much will change as a result (see series of blogs in April analysing potential impact).

Some modest improvements have been made to existing provisions in the Bill. But improving the design of ineffective policy mechanisms is hardly much to celebrate.

I worked with Monica Lennon MSP to lodge a series of amendments on abolishing the Crown’s archaic property rights, modernising land information systems, protecting commons and repealing 17th century legislation allowing for privatisation of the commons. Most of these issues are of long-standing. None were given much serious consideration by the Cabinet Secretary, Mairi Gougeon. None were successful.

This illustrates one of the problems in seeking to influence Scottish Parliament Bills. By Stage 2, it is too late to expect to be able to incorporate matters additional to those in the Bill as introduced. One has to start very early in the policy making process to stand any chance of influencing matters. Even responding to pre-legislative consultations probably doesn’t achieve a great deal.

It also helps to have insider access and to be able to have meetings with Scottish Government officials and Ministers. In practice, only organisations with staff and resources can put in the kind of effort that is required. Even then, the lobbying efforts of vested interests usually far outweighs the views and evidence of the few people and organisations in Scotland campaigning for land reform.

Given the experience at Stage 2, it is unlikely that any substantial improvements to this lacklustre Bill will be forthcoming before it becomes law.

TWO: Scotland’s ever more concentrated pattern of private landownership

As I revealed in March this year, the pattern of privately-owned rural land is becoming more concentrated.

Analysis of the data relating to large scale (<500 ha) rural land sales (published here for the first time) explains the reasons for this state of affairs. The table below shows the total amount of land held in holdings of over 500 ha changing ownership in each year from 2020 to 2023. It includes parcels smaller than 500 ha where these are being acquired by an owner who already owns over 500 ha or who, as a consequence now does.

Large scale land sales >500ha

| 2020 (ha) | 2021 (ha | 2022 (ha) | 2023 (ha) | TOTAL (ha) | |

| New Owner | 24,659 | 4794 | 13,270 | 29,467 | 72,190 |

| Existing Owner | 21,476 | 19,261 | 19,298 | 25,939 | 85,974 |

| Total | 46,135 | 24,055 | 32,568 | 55,406 | 158,164 |

| % Existing Owner | 46.6% | 80.1% | 59.3% | 46.8% | 54.4% |

Each year’s total extent of such land is broken down by how much has been acquired by new owners (those who do not already own any land in Scotland) and how much has been acquired by existing landowners. The bottom line shows the percentage of the total extent that was acquired by existing owners. The results show that over the four years, 54.4% of the extent of all such land transactions was acquired by those who already own and and are expanding their landholdings.

It would be possible (though time-consuming and complex due to how the Land Register holds historic information) to conduct this analysis for previous years. But from my understanding of the land market, this is a trend that dates back to 2010 or so. It is this expansion of existing holdings that is driving the recent re-concentration of private landownership.

In the media release published on 14 March 2024, when the Bill was introduced to Parliament, the Minister responsible (Mairi Gougeon) claimed that,

We do not think it is right that ownership and control of much of Scotland’s land is still in the hands of relatively few people.

Opening the Stage One debate in Parliament, The Minister claimed that,

In Scotland, we have one of the most concentrated patterns of land ownership in the world, with 421 landowners owning 50 per cent of privately owned rural land. We are an outlier in comparison with Europe, where more diverse land ownership is the norm. That long-standing unfairness and the negative impacts on our rural communities have previously been raised by the Scottish Land Commission and others. Scotland’s land must be an asset that benefits the many, not the few, and it must play a leading role in sustaining thriving rural communities, tackling the climate change and environmental crises and continuing sustainable food production. [1]

I agree with her.

Which makes it all the more puzzling that when it came to giving effect to those rhetorical claims, she refused to do so, claiming that there is no evidential base for them.

I highlighted this in a blog following the conclusion of Stage One scrutiny. Here is a flavour of the exchange between the Minister and Michael Matheson MSP.

Michael Matheson: If we get to the point where someone is the third-largest landowner in the country but does not have a land management plan to their name, while someone who happens to have one piece of land that is just over the threshold has to go to the extent of having a full land management plan, there will be a real inequity to that. That needs to be addressed.

Mairi Gougeon: We would have to give greater thought to how that could be done and to the evidence base that we would use if that was to be the proposal.

During the Stage 2 debate on amendments from Mercedes Villa MSP that would have removed the requirement for landholdings to be contiguous in order to be within the scope of the Bill, the Minister argued again that,

the evidence base that underpins the bill as introduced focuses on the concentration of ownership and its impact on local communities. We do not have the evidence base to justify measures that tackle aggregate holdings across Scotland [2]

For decades, SNP politicians have lamented (as Mairi Gougeon herself did above) the concentrated pattern of Scotland’s landownership. It has been a perpetual complaint made as far back as the 1990s in the UK Parliament by Alex Salmond and Roseanna Cunningham among many others.

And yet, despite holding unprecedented political power in Scotland since 2007, not one of them has done anything about it, leading to the embarrassing spectacle of Ms Gougeon saying that she hasn’t got the evidence she needs to do anything about it. If that is the case, why on earth did she feel able to stand up in Parliament 3 months earlier and claim this was so wrong? Here is the Stage One quote above repeated with my emphasis.

In Scotland, we have one of the most concentrated patterns of land ownership in the world, with 421 landowners owning 50 per cent of privately owned rural land. We are an outlier in comparison with Europe, where more diverse land ownership is the norm. That long-standing unfairness and the negative impacts on our rural communities have previously been raised by the Scottish Land Commission and others.

I have yet to get to the bottom of why Ministers appear taking this stance. It is certainly bound up with the (at times rather opaque) advice from the Scottish Land Commission and how Ministers have chosen to interpret it. It is also associated with attempts to disentangle the relative impacts of scale and concentration together with the apparent conclusion that concentration only matters when it impacts communities directly. The 1000 ha threshold is a rather arbitrary threshold being used as a proxy for concentration but has far more to do with not upsetting the National Farmers’ Union of Scotland than with any rational analysis. I don’t have the time to explore this further but I do hope someone will do a rigorous analysis of how we got to this point.

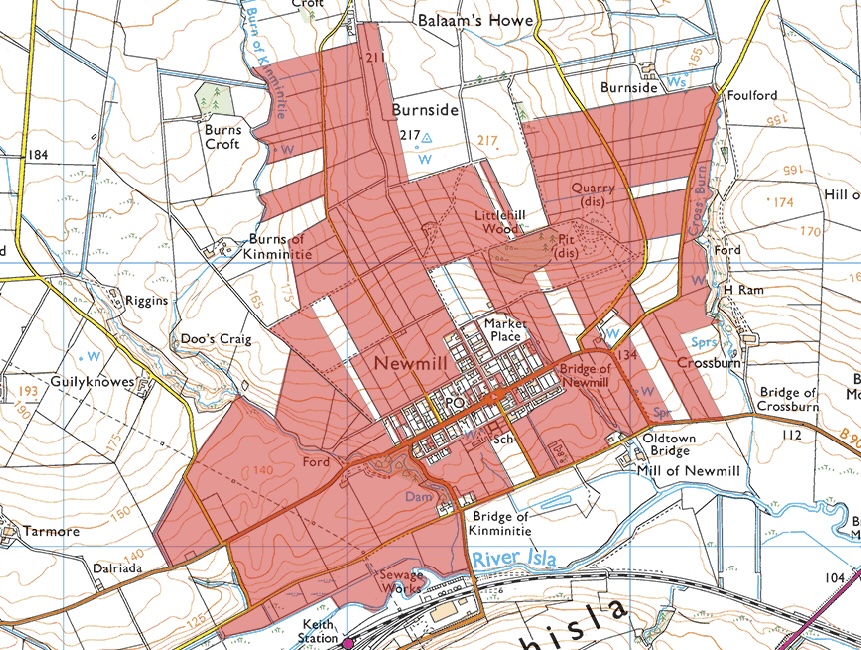

To illustrate the arbitrary nature of the 1000 ha threshold, I have replicated a map at the top of this blog that I first published with no explanation in my Who Owns Scotland 2024 blog.

The maps shows a landholding of 204 hectares in extent around the village of Newmill in Banffshire. Newmill was planned and established in the mid 18th century by the Duke of Fife. The Newmill Estate and village were later sold. Many of the properties in the village are now owner-occupied but if you step onto the village street, you are stepping onto estate land and if you want to buy any land in or around the village you need to deal with the estate. The owners live in New Zealand.

Even if concentration is only a problem when it impacts communities directly, the idea that this is restricted to the less that 5% of people who live near estates of over 1000 hectares is, as this example illustrates, absurd.

THREE: Ongoing Failures in Policy

Exacerbating the failures inherent in the current Bill and its genesis is a longer story of failure in land policy and reform.

In 1999, for example, Jim Wallace MSP, who was in charge of the first land reform Bill, asked the Scottish Law Commission to consider the law of the foreshore and the seabed as part of the Scottish Executive’s land reform action plan. The Commission published its report together with a draft bill in 2003. It included proposals to strengthen public rights in the foreshore and seabed.

In the 22 year since, nothing has been done to implement these recommendations. Had they been implemented, many people and businesses would have benefitted.

In June 2013, the then First Minister, Alex Salmond announced a target of one million acres of land in community ownership by 2020. The policy was dreamt up in Mr Salmond’s ministerial limousine on the way to Skye since a previously planned announcement had fallen through. A few years later the target was quietly dropped (there are currently 545,000 acres of land in community ownership).

On 23 May 2014, the final report of the Land Reform Review Group was published. Two days later, the then Minister, Paul Wheelhouse, committed to completing the Land Register by 2024 with all public land registered by 2019. Neither target was met and the target has been abandoned.

In its respose to the report, the Scottish Government agreed with some recommendations, disagreed with others, argued that some were already being implemented and said it would consider others further, specifically, that,

A further report will be made to Ministers for their further consideration in 2015

In May 2024, I asked Scottish Ministers under freedom of information for a copy of the report that had been promised on these recommendations. In response I was told that,

The Scottish Government does not have the information you have requested as this report was not produced

So, after committing to consider these recommendations and produce a report for Ministers, it turns out that nothing happened.

In 2015, the then Deputy First Minister, John Swinney, announced that the Government would develop a land information system for Scotland providing a “one-stop shop for land and information services”. A report was presented to him in July 2015 with the goal of establishing the first wave of the service by 2017, the 400th anniversary of the establishment of the Register of Sasines. Apart from internal improvements to the Registers of Scotland own land information, no such comprehensive service has been delivered. [3]

These are just some examples of the whimsical nature of land reform policy. Proposals have been made and commitments entered into with great fanfare only to later be dropped, abandoned and, in some cases, not acted upon at all.

FOUR: Where Stands Land Reform Now?

After 25 years of the Scottish Parliament, 17 years of SNP Government, 2 major reviews of land reform policy and the establishment of the Scottish Land Commission (with a budget of £1.5 million per year), the core agenda of land reform – redistributing power over land – is essentially not much further forward than it was in 1999.

Not only has the long-standing issue of land concentration yet to be tackled (and it is gettign worse), but many of the recommendations and commitments made over the years (see above), have not yet been delivered.

It is hard to know how to remedy this state of affairs. There remains an intellectual vacuum at the heart of Government, a failure to engage with the expertise that exists and, above all, an ongoing failure to connect with the myriad ways in which this agenda directly affects people.

For example, nothing in this Bill nor in any other policy proposals does anything to deal with the following issues, all of which are contemporary problems.

- the exorbitant fees being demanded by the monopoly owner of a Scottish island to secure servitudes to deliver electricity and water to islanders’ homes;

- the draconian restrictions being placed by some monopoly owners of the foreshore;

- the ludicrous tax system whereby some landowners pay more land tax to foreign countries than they do to Scotland;

- the growing external extraction of wealth from Scotland’s land for external capital including the state investment banks of France and Japan;

- the lack of control so many communities have over land and property that has belonged to them for centuries (common good land);

- the ongoing expropriation of common land

- the ongoing disadvantage faced by women in particular due to Scotland’s outdated inheritance laws.

- the concealing of prices paid for land by external “investors”.

- etc…….

Land reform is difficult.

It involves challenging vested interests

It requires serious, sustained application of intellectual and political resources.

The rewards are substantial but the past quarter of a century have betrayed the hopes of many who campaigned for a Scottish Parliament and who assumed that the land reform project would have been treated more seriously.

It is hard not to conclude that meaningful land reform that democratises land, modernises the land tenure system and promotes fairness and opportunity is as far away as it has ever been.

NOTES

[1] See Official Report of the Stage One debate (Col.34) and watch here.

[2] See Cols 49-52 of Official Report of Net Zero Committee 3 June 2025 for discussion

[3] See the report I wrote for David Hume Institute and Built Environment Scotland for further discussion.

Excellent report re Land Reform in Scotland ( or lack of it)…It makes depressing reading particularly when those representatives who should be defending our land are doing nothing. They seem to be aware of the parlous state of land ownership in Scotland but do nothing. It must feel like walking in glue.

I want to draw your attention to an email I received from Believe in Scotland. They have produced a booklet advertising all that is good in Scotland..otherwise how would we know as the foreign english centric media so often criticise Scotland…unfairly. But how would the person in the street find out that we are not too wee too poor too stupid as you often hear Scots repeat.

They point out in an email yesterday that Scotland is a powerhouse in international exports for food and drink… that drives the UK economy . Scottish exports…£1,300 per person in Scotland..England..£200 per person.

If your information re Land Reform was included it would let the ‘person in the street’ what is going on with land ownership in Scotland. I only know because of your hard work.

I also read theTax Research blog by Richard Murphy. He writes for the National as well. Last week someone asked about land ownership in Scotland. ( an englishman). I was able to mention you and some of the details you had reported on. Might be worth reading this blog ..and you would be able to put details out there. Scots need to know exactly what is going on and would be shocked if they read your reports.

Just some suggestions. Thank you for all your very hard work .

Cheers

Cathy McNamara

Enlightening piece. Can I suggest it needs two things: 1. A short statement of some ambitious but achievable goals. 2. A call to action eg an organisation that people can join where efforts will be coordinated.

1. I piublished an outline of a bill in December 2023

2. There is no organisation in Scotland co-ordinating land reform

Some of this is down to the unverified evidence used as the basis of ‘research’ on scale etc of ownership organised by the Land Commission in 2018. Despite that weak report, which has been the basis of much woolly thinking since, the report did say that Concentration of ownership was a bigger issue for land reform than ‘mere’ Scale, and that remains true. Crafting a sensible legislative intervention for concentration issues is not easy, ( and the comments about ‘ransom strips’ in the 2014 (Dr Elliot’s?) Land Reform report are relevant to this) but sorting that out would be a big advance.

Charging the Scottish Government’s Agricultural Troughs Directorate with delivering on the SNP’s manifesto commitment on land reform gives an indication of the strength of its commitment.